Ralph Papakhian and Technological Transformations of the 1980s: A Personal History

The following is an expanded version of the text for a video presentation given by Richard Griscom at the annual meeting of the Midwest Chapter of the Music Library Association on 21 October 2021. This version includes anecdotes that, because of limits on time, were omitted from the presentation. The shortened version of the text, as presented, is also available.

Last year was the tenth anniversary of Ralph Papakhian’s death, and I’d intended to write a remembrance of him to mark the occasion but didn’t because I got caught up in working from home and adjusting to life during the pandemic. Once I retired at the beginning of this year, I finally had some time to think and write about Ralph and his influence, and I thank the program committee for letting me share this personal history with you. I was a member of the Midwest chapter for twenty-three years before I moved to Philadelphia in 2004. Many of you are former colleagues and students—and friends—and it’s good to be with you again.

I got to know Ralph in the 1980s, when library technology was going through some transformational changes. Over the course of a few years, we saw the introduction of shared online cataloging, the online public catalog, and electronic mail, and these new technologies changed the way librarians did their work. The early 1980s marked the beginning of a period of technological innovation that continues to this day. I want to talk with you about Ralph’s influence on me—influence that many of you also benefited from—and I want to give you a first-hand account of the what it was like to live through these changes in the 1980s. And I’ll close by reflecting a bit on the equally transformational changes of the past decade—changes that Ralph unfortunately didn’t have the opportunity to experience.

I was sitting in the library working on a class assignment when I first saw Ralph Papakhian. He was standing at the card catalog on the other side of the room, and his unkempt black hair, roughly parted on one side, and his wiry beard had caught my attention. I imagined he was a young assistant professor, but it puzzled me that I hadn’t encountered him before. He pulled a sliding shelf out of the center of a broad array of card-catalog drawers, looked at the labels on a few, pulled a drawer out, and set it on the shelf. Using both index fingers, he quickly flipped through the cards, looking only at the ones that for some reason were sticking out above the others. At one point, he grimaced and pulled a card out of the drawer, flipped ahead a few cards, and reinserted it. After he had reached the end of the drawer, he did something I’d never seen: he lifted the round knob on the front of the drawer and pulled out a metal rod attached to it. The cards that had been sticking above the others fell into place, and he reinserted the rod.

Who was this man, and by what authority was he pulling out drawers, moving cards, and removing rods?

Sycamore Hall, Indiana University, which housed the music library from the 1970s until 1996. (Photograph from Indiana University School of Nursing website)

I had moved to Bloomington, Indiana, in fall 1978 to begin a master’s program in musicology with a minor in percussion at Indiana University. As a musicology student in the days before online databases and e-books, I spent a lot of time in the music library, which at that time was located in the basement of Sycamore Hall, a building constructed in 1940 as a women’s dormitory. Like nearly all buildings on IU’s campus, it was made of gray Indiana limestone, which, in the winter, when set off by dirty white snow, amplified the dreariness of the season. The academic music faculty had offices in former dorm rooms on the upper floors, and the music library was in a cramped, warren-like space in the basement. Pipes in the ceiling periodically burst and sprayed water onto parts of the collection. I remember on one of these occasions seeing David Fenske, the director of the library, walk in to survey the damage then leave after a few minutes in a posture of defeat but with fury in his eyes. A little over fifteen years later, the library moved from Sycamore Hall into a renovated space in the large Education Building on the other side of the Music Annex’s round silo, and a few years after that, David left Bloomington for Philadelphia to become dean of Drexel University’s library school.

When you walked into Sycamore Hall, the entrance to the library was on the left. Beyond the glass entry doors a dozen stairs descended to a basement level. The high ceiling of this first room made it seem more spacious than it was. On the left side was a maze of shelves holding the reference collection, and beside them was a long table for readers. On the right side of the room were the card-catalog units.

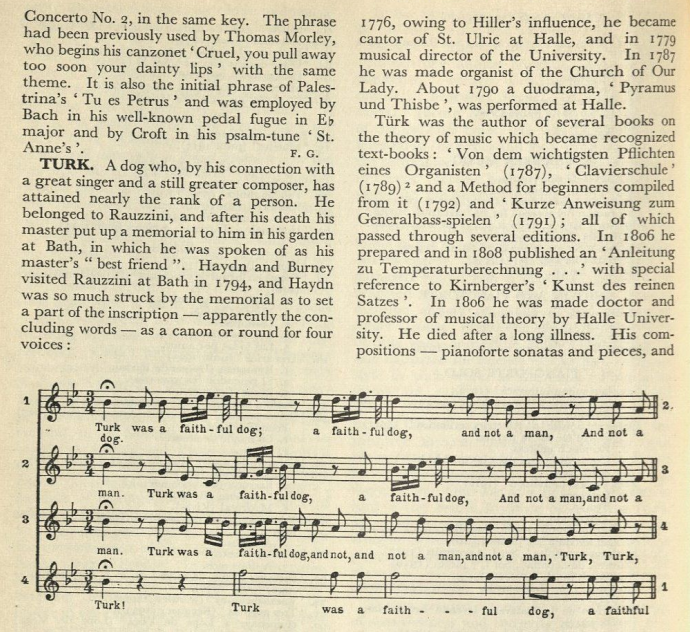

I was one of four or five students entering the musicology program that year. A required class for all of us—along with the doctoral music performance students—was David’s course on music bibliography and research methods. In the late 1970s, music reference sources were available only in print, so the core of David’s course was a survey of the books shelved on the left side of this first room. The students in David’s class spent hours at the long table, working their way through the week’s assigned reference books, which usually numbered over a dozen, printed on a mimeographed handout. We pulled each volume from the shelf, examined it, and took notes. There were assignments that sent us on treasure hunts, searching through that week’s books for the answer to a question like, What was Haydn’s relationship to a dog named Turk?

Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 5th ed., ed. Eric Blom, 9 vols. (London: Macmillan; New York: St. Martin’s, 1954), s.v. “Turk.” (Photo credit: Paula Hickner). A footnote explains that the article, written by Sir George Grove and “probably the only one on an animal appearing in a musical dictionary,” was “omitted after the second edition, but was restored to the fourth at the urgent request of several correspondents.”

The standard English-language encyclopedia of music was the fifth edition of the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, which had been only partly updated since the 1950s. The arrival of The New Grove in 1980 was a landmark event, and the library purchased three copies, including one for the cataloging department. Faculty laid out over a thousand dollars to own a personal copy. During the week after his copy arrived, A. Peter Brown spent his evenings at home slowly paging through the twenty volumes page by page.

I was sitting at the long table taking notes on a book when I saw Ralph standing at the card catalog and puzzled over who he was and what he was doing. Although he wasn’t particularly short, something made him seem foreshortened vertically. Perhaps it was the aura of gravity about him. Or maybe it was his nose, unusually broad at its base, forming an equilateral triangle when looking at him straight on. Over time, I noticed that he wore khaki pants year round with long-sleeved Oxford shirts when it was cool and patterned Columbia short-sleeved shirts when it was warm. I never saw him wear a pair of blue jeans, but on the other hand, I never saw him wear a tie.

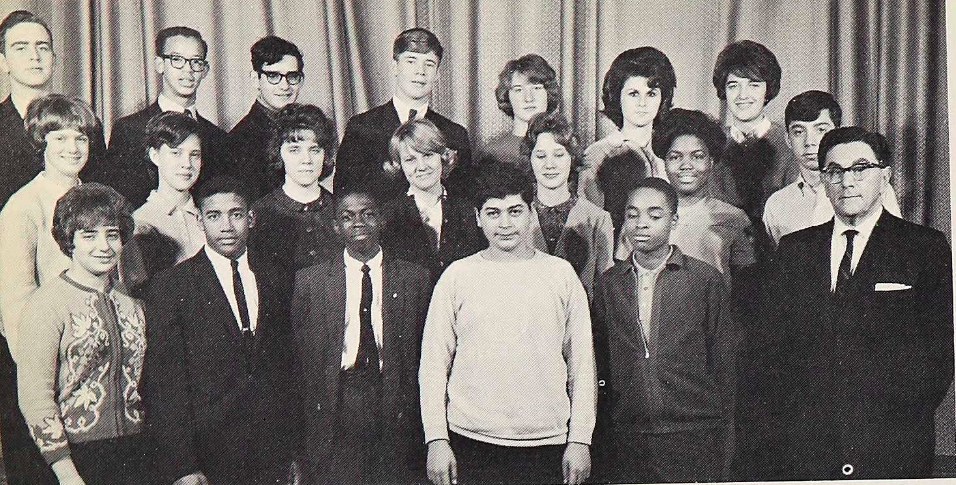

I also learned later that he was Armenian and proud of his heritage. His father, mother, and older brother and sister had immigrated to the United States from Beirut, Lebanon, in 1946, two years before he was born. They traveled by boat from Marseilles, France, to Galveston, Texas, and settled in Detroit, Michigan, where Ralph was born in December 1948. Ralph’s father was fifty-one and his mother was thirty. The family spoke Armenian at home, and Ralph was fluent. He attended Cass Technical High School, where he played clarinet and tenor saxophone. Years earlier, other students at Cass Tech included jazz musicians Paul Chambers, Ron Carter, and Alice Coltrane; singer Diana Ross; comedian Lily Tomlin; automaker John DeLorean; and rock musician Jack White.

Homeroom 617B, Cass Technical High School, Detroit, Michigan, 1964. Ralph Papakhian is in the front row, fourth from the left. (Cass Technical High School 1964 yearbook. Image from Ancestry.com.)

It wasn’t until 1980, two years after my first sighting of Ralph, that I got to know him. The graduate musicology program at Indiana included both a master’s and doctoral program, and the faculty assumed that students completing the master’s program would continue their studies and pursue the doctoral degree. I went through a lot of soul searching during my second year in the master’s program. After spending six years in college, I was growing weary of classwork. I doubted I’d have the stamina or patience to make it through a doctoral program. Yet I had been enjoying my years in college. Indiana University was the only school with five student orchestras, and at certain points in the school year it was possible to hear an orchestra concert each week. The IU Opera Theater staged four operas each year in the Musical Arts Center with elaborate sets and lighting. During the course of the semester, there were dozens of solo recitals and chamber-ensemble programs. As the end of the semester approached, there so many that they were scheduled from early afternoon to nearly midnight. And all of these performances (except for the opera) were free. It was as an invaluable fringe benefit of being at Indiana University. I had spent as little time as I could get away with on the hard work of practicing and studying. Living in carefree bubble, I had attended concerts, played percussion in orchestras and ensembles, and socialized. I wasn’t sure I would be able to adjust my attitude and redirect my energy to meet the demands of doctoral study.

Inside the Musical Arts Center, Indiana University, where the school’s five orchestras performed and operas were staged. (Photograph from the Indiana University website)

As I began to emerge from my dream state, I saw it was time to think about how I might support myself. Several students in the musicology program had earned a PhD with great effort and then failed to get a job. Others were able to land temporary appointments as instructors that provided only a year or two of job security before they had to compete again in the job market.

In an environment like this (and the situation would get worse as the years passed), my chances for landing a steady job in musicology weren’t good, especially considering I hadn’t distinguished myself in the master’s program. I had one reliable supporter among the musicology faculty and was more highly regarded by the percussion faculty than by the musicologists. I had played in three of the five student orchestras—including the top one, the IU Philharmonic—and I was one of the best students of Richard Johnson, IU’s first percussion instructor. I’d considered pursuing a career as a performer, but the chances of my finding steady employment as a percussionist were also slim. I had no trouble practicing an hour a day to become good, but to become competitive as a professional would have required five or six hours of daily practice. I seemed incapable of doing anything—studying or practicing—with that level of commitment.

I learned about IU’s one-year program in music librarianship when a few of my musicology classmates completed it and landed jobs soon after. Music librarianship seemed an appealing option that aligned well with my interests. By the end of David Fenske’s music bibliography and research methods class, I had felt an unexpected enthusiasm for libraries and bibliography. The picky rules around citation style, as laid out in Kate Turabian’s Manual for Writers, had been despised by most students in the class, but constructing bibliographic citations had brought me satisfaction. Describing books in a uniform style allowed me to impose order on at least a small part of the muddle around me. Yes, my desk might be a mess, and two weeks’ worth of laundry might be overflowing the hamper, but as I look down at this citation I typed on my Smith Corona, all the right words are capitalized, and the punctuation is correct. It is a small thing of beauty amid chaos.

Because David was a librarian, I associated the work I had enjoyed in his class with librarianship, and what I had found engaging about bibliography was closely tied to what would later appeal to me about cataloging: the mental work of using a set of rules and the information in reference resources to describe materials consistently and accurately. I asked for a meeting with David to talk about entering the music librarianship program.

When we sat down, he wasted no time. “Why do you want to become a music librarian?” He seemed skeptical, perhaps thinking this was a fleeting whim. The question shouldn’t have surprised me, and although I can’t remember how I replied, I know I didn’t answer it convincingly. Well, I’ve always liked libraries. I enjoyed the work in the music bibliography class. These weren’t reasons to become a music librarian, nor was the reason forefront in my mind, which I left unspoken: I need a job when I graduate. Despite my answers, David admitted me to the program. He might have seen something in me that I doubt was there at that point, or he might have needed to keep a stream of students moving through the program. Regardless of the reason, I was luckier than I’d realized at the time, because this was the path that led me to Ralph.

At the center of Indiana’s specialization in music librarianship was a seminar led by David and taught by all the music librarians. The semester was divided into sections covering several broad topics, and subsets of the library staff taught for a few weeks at a time: David on library administration, Michael Fling and Kathryn Talalay on reference services and collection development, and Ralph and Sue Stancu on technical services.

There were occasional classes where all the instructors met together with the students, and for those, the teachers outnumbered the students, since there were only two of us enrolled in the class. My classmate—a fellow musicology student, far smarter than I but admittedly less engaged in the subject of the course—ended up never working in a library. She pursued a successful career as a promoter of classical music and became the executive assistant of a prominent composer.

We were unenthusiastic students, impatient to get the degree and move on with our lives. When the seminar started in spring semester, we were emerging from our first term as students in the School of Library and Information Science, where the standard of instruction and the expectations for students were lower than they had been in the musicology program. A particularly mind-numbing introductory course in reference service had left us doubting our decision to pursue the library-science degree. We started spring semester with a commitment to soldier on, doing whatever was needed to make it to the end. By the middle of the semester, we had decided that meant meeting up on the stone ledge outside Sycamore Hall to smoke a joint before entering the building for the two-hour seminar.

The five instructors, in turn, showed little enthusiasm for teaching two impassive, burnt-out graduate students. As the semester began, it was clear we weren’t fully present. We did the homework but showed little of the interest and curiosity that inspire good teaching.

Each librarian had a different approach. David was earnest in the classroom. He had established the specialization in music librarianship and touted it as one of his many successes. As he talked to us about managing a library, we heard a lot about accomplishments at Indiana that had burnished his reputation. He enjoyed teaching, and, as I had learned from his music bibliography course, he liked peppering his lectures with puns. “I should be punished for that one,” he would say after a particularly bad one—which meant he said it often.

Michael and Kathy were an odd pair. I first knew them as reference librarians who alternated morning and afternoon shifts sitting at the large, wooden desk next to the reference collection. There was little traffic at the desk, and they passed the hours sorting through selection slips and marking up publishers’ catalogs for searching. Both were brilliant and subsequently made important contributions as authors and editors: Michael with his classic books on collection development and decades of editorial work for Notes, and Kathy with her Composition in Black and White: The Life of Philippa Schuyler and work as an editor at W. W. Norton. They were a study in contrasts. Michael was quiet and dour, which made his scathing sarcasm all the more cutting, especially when directed at the seminar students. Kathy was also quiet but compassionate and encouraging. By making us comfortable and relaxed, she set the stage to ask honest, brazen questions. Similarly, they had different views of the seminar and its students. Kathy understood we were checking a box toward a degree, while Michael seethed over our lack of engagement.

Ralph was recognized as a leader in the music-cataloging community and could have lectured at length about his successful work at Indiana, but he rarely talked about himself. His teaching was Socratic. Class sessions often centered on a cataloging conundrum he had found in his work, and he invited us to think through the problem with him. One day he brought in a score selected at random from a new shipment. “So. How would you catalog this?” We looked at the cover and the title page and threw out some ideas. He thought a while, smiled, and said, “I think I’d put it in the backlog.” In our sessions with Ralph and Sue, Ralph took the lead. Sue had joined the staff only a couple of years earlier, and though she was still learning from Ralph, she knew enough to have strong opinions and would occasionally challenge him in class, which was a time for us students to sit back and enjoy the show.

At IU, there was always a point in spring semester when academic buildings were too hot. The HVAC systems on campus responded slowly to the rising outside temperature and continued to pump hot air into buildings as if it were still winter. For our afternoon seminar sessions that spring, Ralph often opened the windows to lower the temperature and increase the chances we’d all stay awake. One afternoon, a paper airplane flew in through one of the windows. Ralph walked over and picked it up. It was made from a piece of notebook paper and decorated in pencil. He started laughing—his punctuated, guttural laugh—and brought the airplane back to our circle of chairs. Written on the wings were slogans of mock anger: “Down with AACR2!” on one and “No AACR2 in I.U. libraries!” on the other.

A member of Ralph’s staff was behind this prank, and it played on two things: the irksome work of implementing AACR2 and Ralph’s political activism. It was early 1981, and the library had just implemented the new edition of Anglo-American Cataloguing Rules, on January 1. The new rules mandated changes to hundreds of name headings—mostly for the better (from Chaĭkovskiĭ to Tchaikovsky) but some for the worse (from Nutcracker to Shchelkunchik). The timing was bad. Had the move to AACR2 been made a decade later, at a time when most libraries had adopted online catalogs and closed their card catalogs, the heading changes could have been made more simply, through batch changes to electronic data. In 1981, most librarians were only dreaming of computer catalogs, so the AACR2 heading changes had to be applied to cards. Electric erasers with tips that spun like dentists’ drills were in heavy use in cataloging departments across the country. The immensity of the task led most libraries to impose limits on the number of cards they would revise. If a heading change required altering more than a certain number of cards (say, fifty), the cards with the new heading were interfiled with the existing cards, and a plastic-sleeved explanatory card, sticking up higher than the rest, was inserted at the beginning of the sequence to inform people what to expect. Most of this tiresome work fell to staff and students who often didn’t understand the reason behind the changes. “Down with AACR2!”

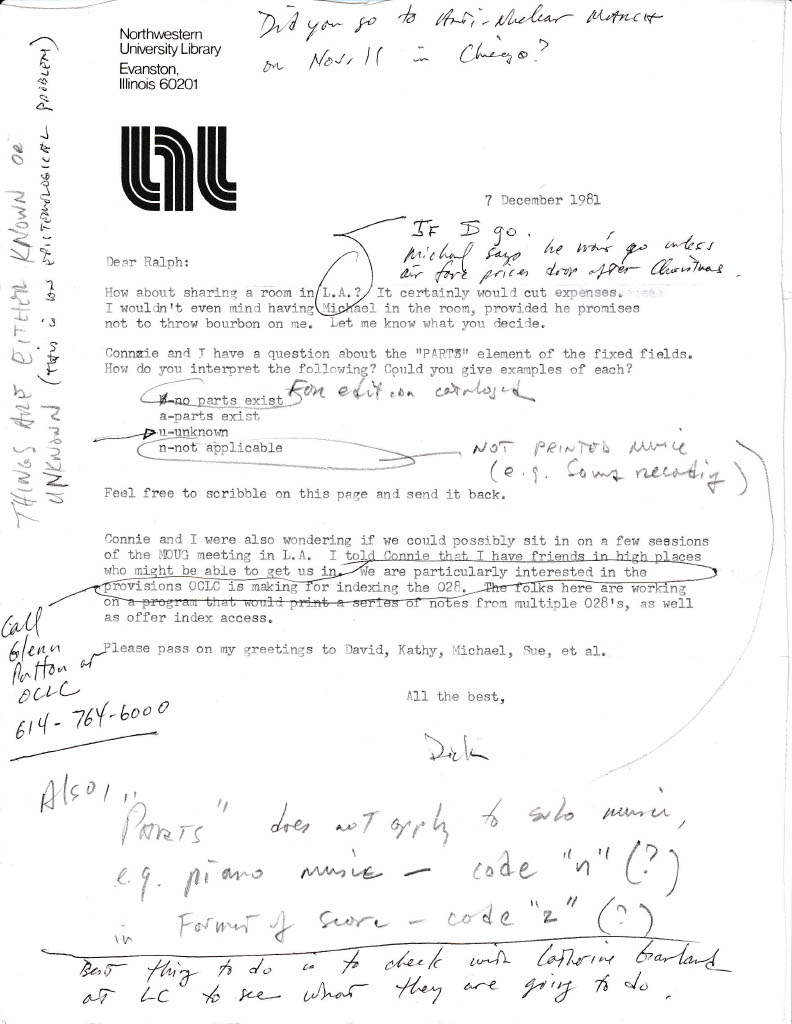

The other target of the paper-airplane creator’s humor was Ralph’s political activism. He was outspoken in his political views, which centered on large issues like American intervention in foreign countries, nuclear proliferation, needless wars, disregard for the environment, and unfair labor practices. He was concerned less about the individual politicians, who come and go, and more about the larger evils that live on. At the start of one of our seminar sessions on cataloging, he asked, “So what do you want to talk about?” Met with our blank stares, he said, “I think we should talk about El Salvador. I’m worried about El Salvador.” A few years later, after I had settled into my first job, I wrote him a letter asking about his interpretation of a MARC data element. He scribbled his opinions on the paper and returned it. Across the top, he wrote, “Did you go to anti-nuclear march on Nov. 11 in Chicago?” I hadn’t gone, but he would have.

Letter from Ralph Papakhian to Richard Griscom, 7 December 1981

By the end of the semester, the instructors were fed up with us. Kathy Talalay told me that in a meeting of the instructors Ralph had made the case for failing both of us, but David had prevailed. We both passed, and because this was graduate school, where anything below an A was seen as failing, I got an A−.

Following the seminar, the specialization program in music librarianship concluded with a practicum, and this was when my admiration for Ralph grew, and I suspect it was also when I redeemed myself in Ralph’s eyes. He started seeing me as something other than the slacker I had been in the seminar, and I started to appreciate the sharp intellect behind the decisions he made as a cataloger.

When you entered Sycamore Hall, if you passed the entrance to the library and continued straight down the corridor, you would find a large technical services workroom on the left and the backlog and rare-book rooms on the right. The workroom was a large open space with no interior walls or moveable privacy panels, so staff sitting at desks were visible to all. Ralph sat near the center of the room at a small desk covered with papers, his copy of AACR2 usually laid open on top of them. An IBM Selectric typewriter rested on an extension perpendicular to the desk. Sue worked on sound-recording cataloging at a desk in the left back corner, and the rest of the nonprofessional staff were nearby. The students and interns sat at a long table at the opposite end of the room. Ralph and Sue smoked at their desks. Ralph had recently switched from cigarettes to a pipe, lending him an avuncular air.

I learned to catalog in this workroom. Ralph assigned me a stack of scores, and I worked on the description and access points at the table in the corner. Near the end of the day, Ralph called me to his desk, and we reviewed my work, discussing each element, its punctuation, and its coding. It was a slow, careful process. Some days the demands of his own work disrupted our schedule, and after apologizing for putting off the daily review, he spent the afternoon tapping rapidly on his Selectic. From the corner table, I continued to catalog and occasionally looked up to watch the machine’s spinning ball bob and jerk across the platen as a thread of smoke rose from his pipe, which he had set near the edge of the desk.

During one of our review sessions, I presented a problem I couldn’t resolve from my reading of AACR2 or the Library of Congress’s many rule interpretations. We discussed a few possible solutions, then we paused to think. He said, “In the heat of the cataloging moment, what would you do?” I laughed, because the idea of heat—heightened emotion, anxiety-provoking pressure—was far removed from Ralph’s own process, in which there seemed to be no sense of urgency, no sense of time. Cataloging was an intellectual pursuit that was to be allotted as much time as needed. Carpenters say, “Measure twice, cut once.” This was Ralph’s approach to cataloging. Time and resources are saved if work is done correctly the first time, and if the work is worth doing, it’s worth doing right.

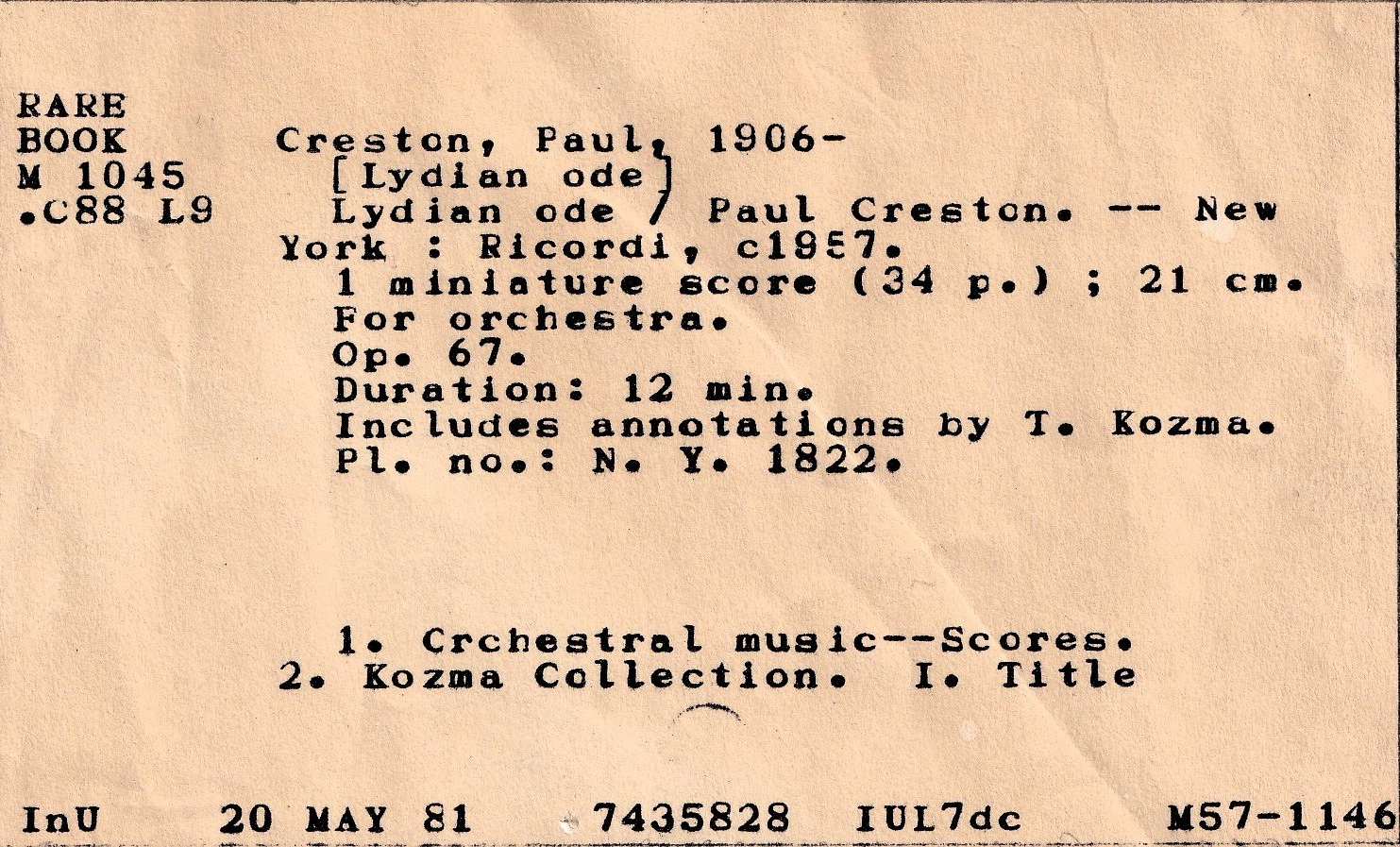

Card for the IU catalog printed by OCLC from Griscom’s first cataloging record, 20 May 1981

With Ralph’s guidance, I contributed my first cataloging record to OCLC, for the miniature score of an orchestra work by Paul Creston, Lydian Ode (1956), marked by conductor Tibor Kozma, who had been a member of IU’s faculty. Kozma’s collection had been donated to the library after his death in 1976, and Ralph had found the score among the unprocessed materials in the cataloging backlog room across the hall. The Library of Congress had cataloged a copy of the score in 1957, and I found a reproduction of the catalog card in one of the National Union Catalog volumes in the workroom. I was obligated to make use of LC cataloging whenever it existed, so I stapled the photocopied card to a sheet of scrap paper, and, working with Ralph, I enhanced the cataloging to describe IU’s copy. The last step was to mark up the cataloging with fields, indicators, and subfields for entry into the OCLC database.

Since 1976, libraries had been creating machine-readable cataloging (MARC) records for music materials. For the time being, the data was used to print cards that were filed in card catalogs, but there was an expectation that some day libraries would develop online catalogs using this data, and these online catalogs would allow users to search for materials in ways that weren’t possible using a card catalog—for example, by searching on individual words in a catalog record, not just on the author, title, or subject.

At Indiana, there was one OCLC terminal for use by the entire department, and this terminal was the point of entry for all cataloging records. Catalogers did their work on paper, and staff, working in shifts, keyed the data into OCLC using the terminal. A lot of time went into the creation of these MARC records, which included information beyond what had been supplied on cards; in some cases, the data elements had no present utility. We added fields like the 048 (Number of Musical Instruments or Voices Code) and 047 (Form of Composition Code) assuming that users would eventually be able to use them to limit search results by certain combinations of instruments or certain musical forms. In the end, the potential of most of these coded data fields was never realized.

By the time I completed the cataloging practicum, I had gained a nominal degree of respect from Ralph through our exchanges at his desk. And we had gotten to like each other. When we ran into each other at concerts, we had long chats. He ended up serving as a reference for me when I started applying for jobs.

In fall 1981, a few months after graduating, I got my first job at Northwestern University, and I brought with me Ralph’s high standard for cataloging. For months, I created beautiful catalog records that I was proud of because they met Ralph’s standards, but before long, my ideals were confronted by the demands of the real world. Hundreds of scores were coming into Northwestern’s Music Library each month thanks to the vision of Don Roberts, the director of the library. When he arrived in the late 1960s, he set as a goal to elevate the music library to the status of a “distinguished collection” (there were already three of these collections at Northwestern), and he saw a few ways to accomplish this. Acquiring rare music materials would be an obvious but expensive way to do it. Another would be to acquire less expensive yet important materials that few other libraries were collecting. Knowing he couldn’t compete in the first area with established, deep-pocketed libraries, he settled on the second, less expensive approach. He built a world-class collection of contemporary music, acquiring scores and recordings for as many newly composed works as possible, and he succeeded in convincing the library administration to increase the music library’s budget to make this possible. The approval plans he set up with Harrassowitz and European American Music yielded large boxes of scores that included not only works by composers that were being collected incompletely by most libraries but also works by a lower tier of composers that no library was collecting regularly. Some publishers and composers in this category became the object of jokes around the office—for example, Seesaw Press’s mimeographed scores bound in brightly colored construction-paper and the steady stream of new works by Tommy Joe Anderson published by Dorn.

With shipments of scores arriving in several large boxes each week, my cataloging staff had a hard time keeping up. The staff used other libraries’ cataloging when it existed—and when we we had access to it. Northwestern at this time wasn’t a member of OCLC, so we draw on the cataloging contributed by its hundreds of member libraries. We were left with the cataloging contributed to RLIN (the Research Libraries Information Network) by a much smaller set of libraries. Still, because most of the scores coming to Northwestern weren’t being collected by other libraries, we were left on our own to create original cataloging for most of them. Following Ralph’s standards, I had been pushing through no more than a few each day, which seemed a pitiful effort.

I arrived at a compromise: retain Ralph’s standards for accuracy but pare down the amount of information included in the cataloging record. The content would be stripped down to essentials, but what was there would be reliable. After I drew up the guidelines for this “minimal-level” cataloging, I trained student workers to do it, and our output increased tenfold. Instead of spending my time creating and curating my own original cataloging, I reviewed and edited dozens of brief records each day. It wasn’t a compromise I liked, but without the addition of more staff, it would be the only way to ramp up the rate of cataloging. Even that wouldn’t match the flow of scores into the library.

A few months after I began working at Northwestern in August 1981, I attended my first MLA Midwest Chapter meeting, in Oberlin, Ohio, and started meeting many of the music librarians that I had known only through their articles or seeing them mentioned in the MLA Newsletter. Among them was Richard Smiralgia, head of music cataloging at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. During the 1980s, Richard became recognized as an authority on music cataloging through the publication of several articles and books, including the confusingly titled pair Cataloging Music (1983) and Music Cataloging (1989). (One is a manual on cataloging music using AACR2, and the other is a broader survey of the history and theory of cataloging music, but like many other people, I can’t remember which is which without looking them up.) Richard had gone to school at Indiana University and worked under Ralph before taking a job at the University of Illinois, where he was the head of music cataloging. He was only four years younger than Ralph. During the 1980s, and until Richard moved to New York City in 1986 to teach at Columbia University, Ralph and Richard were considered the two experts on music cataloging, and people often confused them—both were dark-haired, bearded catalogers with names that start with R at two universities that start with I. Music catalogers rarely confused them: Richard was a researcher and theoretician who wrote about cataloging and contributed to the development of cataloging policy, and Ralph was primarily a practitioner who taught library-school students and hosted popular summer cataloging workshops. Richard eventually left the field to teach and pursue research on the idea of “the work,” but while he was still at Illinois, he and Ralph collaborated on a 1981 article for Notes that analyzed score and sound recording content in the OCLC database (“Music in the OCLC Online Union Catalog: A Review,” Notes 38, no. 2 (December 1981): 257–74). The article won MLA’s Richard S. Hill award in 1983, and Ralph later won a second Hill award for “Cataloging,” his contribution to Music Librarianship at the Turn of the Century (Notes 56, no. 3 [March 2000]).

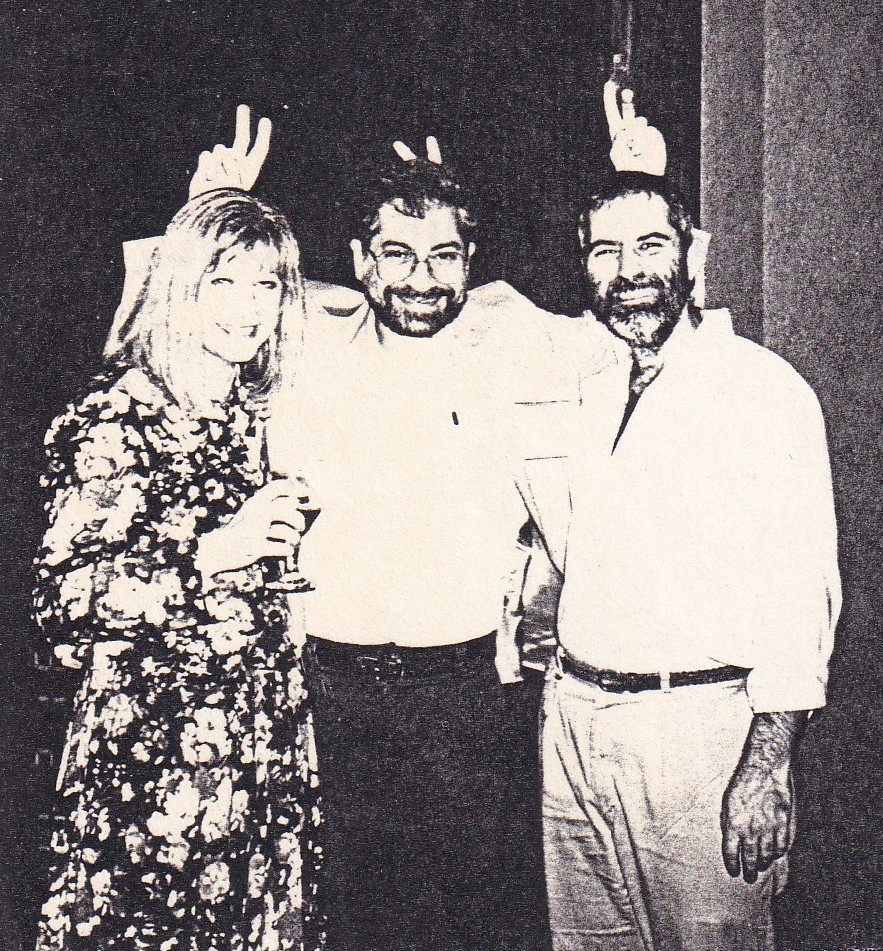

Left to right: Deborah Campana, Ralph Papakhian, and Richard Smiraglia at the MLA Annual Meeting in Tucson, Arizona, February 1990. (Photocopy of photograph by unknown photographer)

While the chapter meeting in Oberlin included presentations, and there were a few chapter committees that met, it was mostly an opportunity to meet and talk with other music librarians. A few months after the Oberlin meeting, I attended my first annual meeting of MLA, in Santa Monica, California, and I saw that this was where music librarians came together to work on the issues facing the profession. There was a lot to discuss in the early 1980s, as the profession worked out the kinks in AACR2 and started thinking about the functionality music users would need in an online catalog.

Steve Fry and his Southern California colleagues put together receptions and entertainment, including a keynote address at the banquet by Nicholas Slominsky, whom Steve had to gently coax from the podium in order to make way for a group of singing UCLA students. Steve was met with a few scattered boos.

I sat in on committees meetings related to cataloging chaired by Richard Smiraglia. At the business meeting, someone proposed a resolution to call on the Library of Congress to finally start using the MARC format for music it had published in 1976. At that time, the Library of Congress was a leader in the music-cataloging community. LC was the de facto national library and held a position of respect and authority. It had one of the largest music-cataloging staffs in the country, and they produced cataloging we relied on.

By the early 1980s, music librarians had grown frustrated with the LC’s delays in implementing the MARC music format. LC continued to issue cataloging for music and sound recordings only on cards, and the delay meant more work for those librarians already cataloging online. LC didn’t begin distributing MARC records for its music cataloging until early 1984—eight years after the format had been published.

In the meantime, the music catalogers using OCLC had moved forward on their own and set the direction for the use of MARC. In 1976, a group of MLA members met several times with OCLC to advise them on music workforms, printing catalog cards, and input standards, which led to OCLC’s publication of guidelines for cataloging scores and sound recordings. Within a few years, shared music cataloging in OCLC had achieved critical mass.

MOUG Newsletter, April 1982

In 1982, Richard Smiraglia was chair of MOUG, and Ralph was completing his third year as editor of the MOUG Newsletter, which had become an important resource for music catalogers. Catalogers turned to OCLC and MOUG for guidance in this new online environment. LC retained control over the development of cataloging standards and policy, but leadership in helping members of the catalog community adapt to new ways of doing their work fell to grassroots organizations like MOUG.

Santa Monica was the first of dozens of annual meetings I’d attend. Although the meetings weren’t expensive—especially compared to meetings in other fields—institutional funding wasn’t sufficient to cover the cost, and my salary as an entry-level librarian was low. To minimize out-of-pocket expenses, Ralph, Michael Fling, H. Stephen Wright (music librarian at Northern Illinois University), and I shared a room at these conferences beginning in 1983. Ralph referred to us as the Gang of Four.

Rooms in convention hotels provided no more than two beds—usually queens, but sometimes doubles. Because it wasn’t customary for unattached men to share a bed (this didn’t seem to be such an issue among women—at least among music librarians), we would try to arrange for a roll-away bed to be added to the room. Often that wasn’t possible, so we were left working with the two beds. At the end of the day, after the drinking and conversation had ended, we pulled the mattresses off the box springs and arranged them on the floor. Ralph and Michael, being the senior members of the gang, slept on the mattresses with the blankets. Steve and I were each left on a set of box springs with a sheet. When we were able to secure a roll-away bed, it went to one of the senior members, and the other senior member slept on an intact bed. Steve and I flipped a coin to see who got the mattress on the floor, with the loser left on the box springs. In the morning, we’d reassemble the beds and pile the sheets and blankets on top. I imagine the housekeeping staff were puzzled by pile of bed linens, but I’m sure they’d seen far worse.

Juggling bed parts was one way we could save save money. Another was to book a room in a cheap motel near the convention hotel. I remember a sketchy motel in Louisville a few blocks from the Seelbach Hotel, where the MLA meeting was being held in 1985. When it was time to check out, the four of us piled into the small office, and the haggard manager produced the invoice. Ralph looked it over and said, “Could we have separate bills? We need them to get reimbursed.” The manager sighed and stared at us. I doubt we resembled his usual clientele: a swarthy Armenian with wild hair, a man with a trim beard wearing a black velvet jacket, and two geeky white guys in tweed jackets. “If you ever stay with us again—and we hope that you will—please let us know this when you check in.”

The 1983 MLA meeting in Philadelphia was held in a Hilton hotel across the street from the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. The Gang of Four chose to stay at the Hilton because there were no cheaper options within walking distance. We were left to find other ways to save money, and eating on the cheap was one of them. When I returned to Evanston, the library director at Northwestern asked me if I’d had any memorable meals in Philadelphia. I thought for a moment. “Well, not really. We ate most of our meals in a hospital cafeteria across the street.”

Between meetings, Ralph and I stayed in touch through letters and phone calls. While unpacking the office files I’d brought home after retirement, I came across a series of file folders holding correspondence, labeled by year. They started with 1981, the year of my hiring at Northwestern, and ended with 1989. Among the various interoffice memos from librarians and administrators at Northwestern, I found letters from Richard and Ralph answering questions about music cataloging I’d sent them (including the letter reproduced above).

I was puzzled at first that I found no correspondence folders after 1989, but I remembered that in the mid-1980s, nearly all my correspondence migrated to email. Ralph and I had been early adopters. Although I had a computer terminal in my office at Northwestern, it was connected to a local network for access only to our library system for cataloging, and it would be several years before I could read email from my office. To do that, I had to leave my office in the music library and walk several hundred yards to the main library, where in a short, dark hallway leading from the card catalog room to the current periodicals room, there were half a dozen VT100 terminals connected to a VAX computer in the Vogelback Computing Center a few buildings away. These terminals were used mostly by computer science majors for programming, although a few students wrote papers and articles on them using a rudimentary word-processing system. Email accounts were available on the VAX by request only, and I was among the first people in the library to get one. At lunchtime and on breaks, I walked over to the shadowy hallway to log into the VAX and check for new mail. During those early days, I got email only from Ralph, and I suspect he didn’t get much email from anyone but me.

The Digital Equipment Corporation VT100 terminal

Northwestern and Indiana were both members of the BITNET network, a cooperative group of educational and research institutions that agreed to support network “nodes” for exchanging email and files between mainframe computers. When I sent an email to Ralph over BITNET, notifications appeared on the terminal, tracing the email’s progress from NUACC (Northwestern) to IUBACS (Indiana University). The name of each node displayed in blueish-white characters scrolling down the black screen as the email traversed the network. At times, nodes would be down, and my email would be stuck for hours until the node had been restored. It was touch and go, but it was exciting.

As more music librarians started using email, I compiled a directory of email addresses, and Ralph made it available for download from an FTP server at Indiana. The list started with no more than twenty-five addresses, and by the time it was no longer necessary, it included more than one hundred.

The directory became obsolete once Ralph had set up an email distribution list list for music librarians. In the late 1980s, Indiana University implemented the LISTSERV software to support email distribution lists, and Ralph invited me to join him in setting up and administering a list for music librarians that, despite the name “MLA-L,” had no official ties to the Music Library Association. Today, MLA-L has been in use for thirty-two years, and it has endured because it uses one of the few technologies that has remained unchanged since the 1980s: email. It’s simple and boring, but remarkably reliable. (The history of the list is covered in detail in “MLA-L at Twenty,” Notes 65, no. 3 (March 2009): 433–63.)

MLA Board meeting in Louisville, Kentucky, June 1989. Left to right: Gordon Thiel (assistant fiscal officer), Susan T. Sommer (president), Lenore Coral (past president), Ralph Papakhian (executive secretary), and Richard Griscom (fiscal officer). (Photographer unknown)

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Ralph and I spent time on the MLA board of directors, separately and together. He was a member-at-large during 1985–87, and when I came onto the board as member-at-large for the 1988–90 term, he was appointed executive secretary. Early in 1992, I succeeded him as executive secretary. At that point, nearly everything related to the work of the association was still on paper, so he drove down to Louisville in April to drop off a couple of bankers boxes of files, stationery, envelopes, and copies of the MLA membership directory. I had been working at the University of Louisville since 1988, and we agreed to meet on campus, not far off the interstate that he’d be taking from Bloomington. He arrived late in the day, so I invited him home for dinner. We agreed that it would be simplest if Ralph left his car on campus, and I could drive him back to campus after dinner. First, we needed to pick up my sons at daycare. Will was seven, and Tommy was five.

We picked up Tommy at the university’s daycare center and Will at the Brown School, where he had entered first grade. The boys took an immediate liking to Ralph as he peppered them with questions during the thirty-minute drive east to our home in Middletown, Kentucky. I made spaghetti for dinner. Ralph was at ease with the kids; it was clear he had a lot of experience. I remembered that during my last summer at IU, I had run into Ralph and his family at a large community concert in a park. As we talked, his kids milled around and played. “Vahan is a roamer. He walks away sometimes,” he said. He looked around. “There he is. Have to keep an eye on him.” Ralph and his wife Mary had three children at that time, and a fourth was born the following year. In later years, they were foster parents to a number of kids.

After dinner, Ralph suggested playing a board game, and Tommy brought out Candyland. As they played, Ralph kept careful control over the moves, never allowing young Tom to slip in a cheat—something I usually let him get away with. A little later, Will started jumping up and down and behaving hysterically. Ralph said, “Yo, Will! You’re being crazy! I bet you can’t stand on your head on the couch for sixty counts.” Will ran over to the couch and stood on his head as Ralph slowly counted to sixty. Once he had finished, Tommy insisted on being given the chance to stand on his head on the couch while Ralph counted. After dinner and after Candyland, as Ralph and I were preparing to drive back into town, Tommy asked to give Ralph a hug, and Ralph obliged.

When we were back on campus, I pulled up behind his car, parked on the street in front of the Music Building. We took the banker’s boxes from his trunk and moved them to my car. It was dark, and we worked under the orange glow of a street lamp. After we’d finished, we stood on the sidewalk and talked. In the strip of grass between the curb and sidewalk, I saw the snowball heads of dandelions at the end of stems, twisted and curled as if they had been writhing as they died. I pointed at them. “Wow. What’s going on with those?” Ralph looked down and grimaced. “Chemicals,” he said, in his clipped, gravelly voice.

Because my term as executive secretary lasted four years, there was an eight year stretch, from 1988 to 1996, when either Ralph or I was executive secretary. At that time, the convention hotel assigned a number of complimentary rooms to the association as part of the contract, and these were usually assigned to the officers of the association—the president, vice president, and at that time, the executive secretary and treasurer. The Gang of Four was still together during some of these years, and because the executive secretary’s room was comped, all four of us stayed for free, and there were often other perks from the hotel, like a fruit basket and bottle of wine. After our humble beginnings, we had fallen into the lap of luxury. But Steve and I still had to seep on the box springs.

At the MLA annual meetings, Ralph wasn’t a raucous partier, but he enjoyed drinking, smoking, and talking until well past midnight. He preferred hanging out in our room rather than in the hotel bar. Drinking was cheaper in the room, and it was a short trip to the mattress or box springs. His preferred drink was red wine, and he usually brought a bottle or two to the meeting. And we discovered other sources for wine.

During the 1980s and 1990s, the MLA annual meeting would end with a seated banquet. This had been a part of MLA meetings for decades. By contracting with the hotel for a banquet, the association was able to negotiate lower costs in other areas. At these banquets, each of us were served the dinner we had selected in advance of the meeting from a list of two or three options. (A ticket for our entree choice was included in the registration packet and we were expected to place it in front of us on the table.) Before the food was served, waitstaff set bottles of wine on each table—typically a bottle of red and a bottle of white. For a table of ten, this was usually enough. For some tables, it was far more than enough, and half-full bottles would be abandoned at the end of the meal. Ralph quickly noticed this. For several years, as the banquet started winding down and people left (this was before the years of the rock-and-roll after-party), Ralph and a few of the rest of us collected the bottles from around the room and brought them to a central table, where we would sit and drink until we were evicted by the staff, at which point we’d take the bottles back to our room and continue drinking, smoking, and conversing until 2:00 am. Regardless of how late we stayed up, Ralph woke up at 6:00 am to go jogging while the rest of us slept in.

When MLA President Don Roberts awarded Ralph with the MLA Special Achievement Award in 1992 for his “countless efforts to bring the Association into the electronic age of communication,” he alluded to Ralph’s principled stance on political and ethical matters while serving on the MLA board of directors, saying that “Ralph represented the heart of the Association.” As the audience applauded, Don handed Ralph the certificate, and Ralph turned to the microphone to make a few remarks. He began, “I don’t know. I feel more like the diseased liver of the Association.”

Eventually, Michael dropped out of the Gang of Four over a dispute with Ralph. Both of them could be high-minded and stubborn, and the conflict arose over allegiances and trust. Ralph was suspicious of the motives of library administrators and often disagreed with their decisions. As the years passed, he had become less accepting of the directions David Fenske was taking. Michael didn’t feel animosity toward David—at least not to the degree Ralph felt it—and David started putting Michael in charge when he was away. At one point, Michael sided with David on a decision that affected Ralph and the technical services staff, and Ralph felt betrayed and stopped speaking to Michael.

That was the end of the Gang of Four. Steve and I continued to room with Ralph, but only for a few years. Steve moved into library administration at Northern Illinois University and stopped attending MLA meetings. I divorced and remarried, and for a few years, my wife attended meetings with me.

Ralph and I stayed in touch. We remained co-owners of MLA-L and wrote each other when there was a technical problem with a subscriber’s settings or someone was unable to post. Occasionally there were uncivil exchanges on the list, and we’d pick up the phone and talk over the situation before one of us—usually Ralph—posted an email to the list to restore order.

By the early 2000s, Ralph was sick and getting sicker. When I moved to the East Coast and remarried, I saw him only at the annual MLA meetings, when we’d have lunch together and talk at receptions. My wife met Ralph at the 2003 meeting in Austin. She immediately liked him, probably because he spoke to her earnestly, without ego or affect. That was the way he spoke to everyone, to library-school students and to library directors. Ralph’s words came out with intent and purpose, in their own time and without any uhs, ers, or hmms. His voice was low and rough, and his intonation was flat.

At MLA receptions, some people work the room strategically, and they spend no more than a few minutes with one person. I remember a former MLA president who greeted me at the opening reception and then as I talked they started scanning the room behind me in search of someone more important. Ralph was always satisfied talking to whoever was standing in front of him and often spent half an hour chatting with a first-time attendee who had wandered up to him having no idea who he was.

Ralph had no problem talking with me and my wife about his medical issues. Because my wife was a physician, she could read things between the lines of his narrative that I couldn’t see, and it wasn’t good. After one of these conversations, she told me she thought the doctors in Indianapolis had made some bad decisions when he first became ill. Later, as his condition worsened, he traveled to the Cleveland Clinic, where he got better care. Still, he was sick and wasn’t improving. He went through several rounds of chemotherapy. He lost weight and became frail.

Ralph and I always let each other know when we were traveling and would be unable to keep tabs on MLA-L. I sent him an email in December 2009 to let him know my plans for the winter holidays, but he didn’t reply. In January 2010, Sue Stancu wrote to let me know his condition was getting worse. I began drafting an obituary. On January 14th, Phil Ponella sent an email to several of us reporting that Ralph had died that morning. At Ralph’s request, there was no burial, funeral, or memorial service.

The tenth anniversary of Ralph’s death led me to think back not only on Ralph but also on what was happening in the profession during that period when he had a great influence on me. The 1980s were transformational for librarianship. After decades of stasis in the way we did our work, there was disruption, and it happened at a pace that was exciting and challenging. There was more change in those ten years than there had been in the preceding fifty.

The transformation took place through technology, and the changes that started in the 1980s continued through the succeeding decades. The 1980s marked the beginning of a long transition from analog to digital that started with a move from paper to pixels—from the card catalog to the online catalog and from typed correspondence to email.

With the evolution of technology in the 1980s came changes in the roles librarians played in the profession. The scope of the impact of our work shifted from local to global. Ralph Papakhian started the decade standing in front of a card catalog that was seen and used by only the several dozen people walking into Indiana’s music library each day. By the end of the decade, his institution’s cataloging was seen, used, and enhanced by hundreds of people across the world. Imagine someone who enjoys singing in the shower being pushed up to the microphone in a vast, noisy arena. It’s comfortable for some but not for others. Shoved onto the global stage of OCLC, catalogers’ work was exposed, and they quickly established reputations. The work of some was gratefully adopted, while the work of others was shunned.

In the 1980s, technology began offering new the ways for users to access library collections and services. With content no longer tied to physical objects, we started down the path to remote access. As time passed, we were able to share this digital content in larger amounts and at faster speeds. Wired networks of the 1980s and 1990s evolved into wireless networks in the early 2000s, and finally into mobile networks. Computing devices shrank in size and were soon smaller than a paperback book. Once we were using portable devices on wireless networks, remote access blossomed and the locus of teaching, research, and work shifted from a specific place to any place. Resources and services that had been available only in the library before the 1980s were now in our pockets and purses in airports and bars.

Ten years ago, while sitting with my family in a noisy restaurant waiting for food to arrive, my younger son asked what song was blaring out of an overhead speaker. I pulled out my phone, and a few seconds later, I had the answer. My older son, who was then in his twenties, shook his head and said with a smirk, “There are no more mysteries.” Thanks to technology, there are fewer mysteries around the dinner table. It can settle scores but often kills conversation. Also, when we’re used to answering most questions easily, we can feel anxious when we encounter a question that can’t be answered. We start assuming there are quick answers to every question. Some people even end up accepting any answer just to avoid being left without an answer.

Easy information access has made us less patient when looking for answers. Maybe it’s time to step back and reconsider: there are benefits to encountering obstacles and having to take time to arrive at answers. Obstacles force us to pause. And they present opportunities to make other discoveries. Today I can learn about the canon that Joseph Haydn wrote in honor of Venanzio Rauzzini’s dog named Turk while sitting at the breakfast table. In 1978, when I was looking for this dog in the reference stacks at Indiana, the process was far slower, but I ended up learning about more than Haydn’s canon. As I pulled books from the shelf, I was being introduced to research tools, and I was learning how to use them. And while sitting at that long table surrounded by reference books, I saw, across the room, someone standing at the card catalog doing something strange and intriguing—something that would end up changing the course of my life.

Ralph Papakhian and Richard Griscom, ca. 1998. (Photographer unknown)