Chattanooga

Market Street in downtown Chattanooga (5th Street looking north), 1963

My earliest memory is of an illuminated amber Indian head on the hood of my grandfather Griscom’s wood-paneled Pontiac station wagon. I was transfixed by the glowing head as I rode in the front seat, and when I wasn’t looking at the warm light of the stylized plastic head, I was watching the dashboard compass, a black ball suspended in liquid, with cardinal directions and hash marks glowing in a luminous light-green phosphorescence, rocking back and forth as the car jostled. When we turned, the ball stayed in place as if we were turning around its axis, and when we hit a pothole, it shook violently and seemed to laugh at us.

I must have been three years old, because my grandfather died of a heart attack soon after I turned four, and the only memory I have of him was this night ride in his station wagon. We were living in Chattanooga, where my father grew up and I was born, and had recently moved into a house in East Ridge, at 140 Kingwood Drive, southeast of downtown Chattanooga and less than a mile north of Tennessee’s border with Georgia. East Ridge was separated from Chattanooga by Missionary Ridge. Until the 1910s, travel from East Ridge to Chattanooga involved traversing the ridge on steep and winding roads. A tunnel was dug through the ridge in the 1913, and in the late 1920s, work began on a second passage, a set of single-lane, low-clearance tunnels that connected 23rd Street in Chattanooga with Ringgold Road in East Ridge. These tunnels, known as the Bachman Tubes, were our gateway to Chattanooga and the family members who lived there.

“The Bachman Twin Tunnels, Entering Chattanooga, Tennessee, through Missionary Ridge” (image from Digital Commonwealth, Massachusetts Collections Online)

Relatives of my father and mother lived either north of downtown Chattanooga, across the Tennessee River, or southwest of downtown on Lookout Mountain. When we returned from a visit with one of these relatives, we drove through the Bachman Tubes and emerged from the dimly lit tunnel onto Ringgold Road, the main artery through East Ridge. After turning off this road, my father drove one block and turned right, and our house was front and center on a rising slope at the tip of a V formed by a road that split off to the left, circled around to the back of our subdivision, and returned to the front of our house, forming the right side of the V.

I enjoyed lying on the grass and rolling sideways down the gentle hill in front of the house, experiencing a mind-altering dizziness when I reached the bottom. Behind the house was a cottage made of cinder blocks, large enough for one or two people. My father rented out the house for extra income. He didn’t vet these tenants carefully, and I was too young at the time to observe or to care about the succession of tenants, but I was aware of my parents deciding that my father needed to evict a young woman who had frequent male visitors. Years later, when the topic came up, my father said the woman was a prostitute, but it’s possible she simply had the occasional boyfriend over to spend the night, and my father made it into much more than it was.

At one point, the cottage was rented to a single mother with a daughter about my age, and we played together occasionally. One day while the girl and I were upstairs, my mother went to the basement to tend laundry. On the door leading to the basement was a sliding bolt lock—I suppose to prevent someone who broke into the basement from entering the main house. The bolt was kept unlatched during the day, and my parents locked it at night. When my mother was in the basement, the girl and I, bored with playing, came downstairs, and I climbed on a chair and latched the bolt. The tenant’s daughter and I strolled off to play outside.

My mother later told my father that she had knocked on the door for some time and called out to me, but I didn’t respond. My brother would have been born by this time, and I don’t know where he was—probably in a crib or playpen. I’m sure my mother was concerned about him if not about me. After half an hour, she took desperate measures. There was a small casement window near the ceiling of the basement. She broke the window and removed the glass from the frame. Although the opening was small, it was large enough for my mother to squeeze through, and by stacking things against the wall, she was able to get herself in a position to pull herself through the window and make it to the outside of the house.

I probably wouldn’t have remembered any of this if my father hadn’t recounted the story repeatedly during the following decades. It wasn’t a story my mother ever told, out of embarrassment for me or for herself, but my father enjoyed it.

My mother’s Aunt Tot—the sister of her mother—lived at 3501 Berkley Dr. in Red Bank. It was a house made of logs stained molasses brown, held together with mortar painted brilliant white. The house seemed to be lifted from a tale of frontier America. Aunt Tot—born Elizabeth Newman—was married to a taciturn railroad claims attorney, Lewis J. Parker, who spent most of his time in an armchair in an alcohol-induced torpor. Aunt Tot was the supervisor of nurses at Erlanger Hospital and was in the hospital room when I was born in 1956. She was lively, talkative, and full of advice—a mother figure for my mom, whose own mother had died at the age of 51, two years before I was born. Beginning in the mid-1960s, after we had moved to Morristown, Tennessee, my mother and Aunt Tot exchanged letters weekly. Tot’s always began “Dear Daughter.”

Aunt Tot had a series of chihuahuas, but never more than two at a time. They were quivering, anxious, bug-eyed animals whose long nails clacked loudly on the pine-plank floor. One was named Petey and was memorable because late in his life he had a cardiac seizure and Aunt Tot, a nurse with decades of experience, was able to revive him through mouth-to-mouth resuscitation.

Aunt Tot and Uncle Lewis had two sons: Lewis Jr., a soft-spoken college student with a long face that resembled his mother’s, and David, four years younger, a charismatic, blue-eyed charmer with an easy grin. My mother was ten years older than Lewis and sixteen years older than David, so in many ways she was more an aunt than a cousin. When my mother was growing up, Aunt Tot and her family made regular trips to Talbott, Tennessee, to visit my mother’s family: Tot’s sister Grace, Grace’s husband Clarence, and their daughter Mary Elizabeth, my mother.

When we visited Aunt Tot’s house in Red Bank, Lewis was already in college, so we didn’t see him frequently. David, born in 1946, was closer in age to my brother and me, and his easy ways and witty humor were something I aspired to, yet I realized I would never be able to be like him—never be able to radiate confidence and charm at that level. He taught me and my brother how to play chess, and he introduced us to music we didn’t know. It was music that we assumed at the time to be cool, but looking back, Cousin David’s tastes were mainstream: Isaac Hayes’s Shaft, for example. He listened to nothing that wasn’t easily heard on the radio.

David eventually went to law school and settled in Cincinnati, where he raised a family of three. He had a distinguished career as a public defender. I remember overhearing him talking with a defendant on the phone, and when he ended the conversation, I was struck by the warmth of his sign off. “Fare well, Robert.” Not “farewell” in the sense of “good bye,” but “fare well” as in “be well.” As I grew older, married, and had my own family, David and I fell out of touch. I learned from my mother than he was appointed a judge. His first marriage ended, and he married a younger woman, whom I never met. I didn’t see him again before he died in 2004 at the age of 58 after a long struggle with cancer.

When I was in graduate school at Indiana University, David drove me once to Bloomington before driving back home to Cincinnati. This would have been 1979 or 1980. It wasn’t on his way, and I can’t imagine where we both had been to have made this trip together. I needed to get back to campus, and he felt obligated to drive me. I was 23, and he was 33, already on his way to establishing himself as a lawyer. He had to be back to Cincinnati the next day to work, which meant a long night on the road—a two-and-a-half-hour drive from Bloomington to Cincinnati after dropping me off. At that point, both his parents had died. On the long ride, we talked about those early years when we visited his family’s home on Signal Mountain. “At some point I noticed that something happened with your mother,” David said. “With the way your mother interacted with my dad. There was a coolness. She avoided him. And it was sudden. It makes me wonder what might have caused that.” This isn’t something my mother would have talked to me about, but I probably would have asked her eventually had she not died so young, in 1993, at the age of sixty-three. After she died, I didn’t feel comfortable bringing it up with my father, since she might not have told him. It was always possible nothing happened and David had imagined this falling out between my mother and his father. Still, it’s something I wonder about—a story that will remain untold.

————- %%

Two aunts of my father’s—from different sides of the family—lived in separate houses a half-hour drive to the west of us on Lookout Mountain. His father’s sister, Isobel Griscom (1898–1980), was a professor of English at the University of Chattanooga from 1922 to

- When I knew her, she was a retiree living with a friend, Betty, and a cat, Impossible, nicknamed Poss. Although it was never discussed in our family—at least within the reach of my ears—she was lesbian, and Betty, younger than Isobel by at least ten years, was her partner. When the content of the 1950 US Census was released in 2022, I found a listing for Isobel and the woman she was living with at that time, Ruth Perry, who, at 63, was ten years Isobel’s senior. Isobel was listed as the head of the household, and in the “Relationship to head” column, where “husband” or “wife” was usually listed, Ruth is described as “partner,” which must have been unusual in 1950. Through a few internet searches, I learned that Ruth had been dean of women at the University of Chattanooga from 1924 to 1943 and a professor of mathematics. She died in 1955, the year before I was born.

When I was ten or eleven, Isobel asked me to write her a sonnet. She made the request in a motel room, and I was sitting on one of the made-up beds. This must have been during a visit to Chattanooga, after we had moved to Morristown. Our family had grown large enough that none of our Chattanooga relatives could house, so we stayed in motels. I had heard of a sonnet and knew it was poetry but had no idea what made a poem a sonnet and what might be involved in writing one. Within a few hours, I’d forgotten about the request and never considered writing one. One of Isobel’s own sonnets was published in the chapbook that her colleagues at the University of Chattanooga compiled in her honor in 1977, Isobel Griscom: An Appreciation.

Not with Wisdom

Not with wisdom can we bind together

The pale fragments of lovely days

And not with love, though each one weighs

Little in the palm—less than a feather

Dropped when some ruby kinglet delays

Above a sturdy pine, doubtful whether

To stay or fly beyond the misty haze

To loftier trees. He knows no tether

Of time, no fear of void. On wing

He circles one and fills the other;

But we that soar by hope—poor wingless thing—

And to the lowest pedicels frailly cling.

To this prudent shadow that we can never be

Tree or bough we tightly bind our destiny.

She was not warm. Her humor would appear unexpectedly and her smiles disappeared as quickly as they appeared. She was an careful observer, and I occasionally experienced the discomfort of having her eyes on me. She let her thoughts be known, and she didn’t blunt or cushion their sharp edges.

She and Betty visited our home in Morristown in the late 1970s when she was nearly eighty years old. I had just returned from a trip to Europe with the University of Tennessee Concert Choir and had a carousel of slides from the trip—photos of the Lion of Lucerne, a mountain view looking down on St. Moritz, Mozart’s house in Salzburg, Heidelberg Castle. My father set up a slide show in the basement of our split-level house on Hugh Drive, and after he had turned off the lights, I began a droning account of a trip that had been fascinating to me. Once I had finished my long presentation, my father turned on the lights, and I turned to see Aunt Isobel on the couch glowering at me.

The other aunt, Jane Gibbony Kelly Ziegler (1900–82), the sister of my father’s mother (Mary Kelly Griscom (1890–1978)), was a lively woman with a blue-grey bouffant and an effervescent laugh. She was always upbeat, always in motion, always laughing. My father claimed she played the piano by ear, and when I asked him what that meant, he said she had never had a piano lesson and learned to play on her own. I was skeptical at the time and still doubt this was true, but she did play her grand piano without music, in an appropriately flamboyant style. Her hands moved in grand gestures across the yellowed ivory keyboard, and often, at the ends of phrases, octaves ascended in triplets to the tinny, out-of-tune upper register.

Aunt Jane’s home on Lookout Mountain was on East Brow Road, only a few hundred feet from Aunt Isobel’s, but unlike Isobel’s substantial yet modestly appointed home, Aunt Jane’s was an opulent showcase, with large picture windows across the back that looked out east over south Chattanooga and Rossville, Georgia. Glass cabinets held sundry Hummels, knick-knacks, and sparkly objects. She was the widow of Alvin Ziegler, a successful Chattanooga attorney who became a chancellor of the Chancery Court. He had been a first lieutenant in World War I. They had one son, Alvin Jr., born in 1936, when Alvin was forty-five and Jane was thirty-six. I never knew Alvin, who died in 1953, three years before I was born, and I never met Alvin Jr., but we heard a lot about both of them from Aunt Jane.

Occasionally Aunt Jane took us into the city for lunch. As she drove us in her large Cadillac, she talked and cackled and pressed her foot hard against the gas pedal. Once we had been seated at the restaurant, my father would converse with her in a shouting voice because she was hard of hearing, drawing uncomfortable attention to our table, which I found mortifying but escaped any notice by my father.

Visits with our Lookout Mountain aunts usually occurred on Sunday afternoons. The houses were hot in the summer and overheated in the winter, and we children sat in a heavy-lidded torpor on a couch. We never visited both Aunts in one outing, though they lived less than a mile apart. The trips to Aunt Jane’s house were more frequent, perhaps because my father felt more comfortable around her exuberant high energy. Aunt Isobel was often aloof and prickly, and there was an added layer of awkwardness because my father had been a student of hers when he attended the University of Chattanooga in the 1940s.

An early McDonalds, similar to the one in East Ridge, which opened in 1963 (photo: Tim Boyle/Getty Images)

In September 1963, a McDonalds opened in East Ridge on Ringgold Road, seven minutes from our home. It was the first McDonalds in the Chattanooga area. The exterior was cheery and bright, covered with white ceramic tile accented with red horizontal stripes, and two golden arches, illuminated with neon lights, anchored the sides of the small building and extended high above it. The company’s early marketing mascot, “Speedee,” a creepy barrel-chested man with a hamburger for a head, an evil grin, and a wink that looked like a physical deformity, sat high atop of the neon sign. The hamburgers were abhorrent to me—I’d have to turn my head from the chaotic mess of ketchup and mustard on the patty—but like nearly all children, I liked the french fries, and I especially enjoyed seeing them made. In the early years, long before everything was frozen and sent to stores in refrigerated trucks, food was made locally at the restaurants, and the McDonalds in East Ridge had an employee stationed just behind the glass window who sliced potatoes, one after the other, using a manual press. He lifted the handle, raising a metal platform, placed what seemed to me an extraordinarily large potato in the space between the platform above and a grid of blades below, and then lowered the long handle, pushing the potato through the blades. Raw potato sticks, a quarter inch square, fell out the bottom into a pot of water. I watched this while eating from my own greasy paper sleeve of overly salted but perfectly fried potatoes, cooked at that time in lard, and marveled at how I was experiencing both the origin and destination of this wonderful food.

Piano lessons

Red Book from the John A. Schaum Piano Course

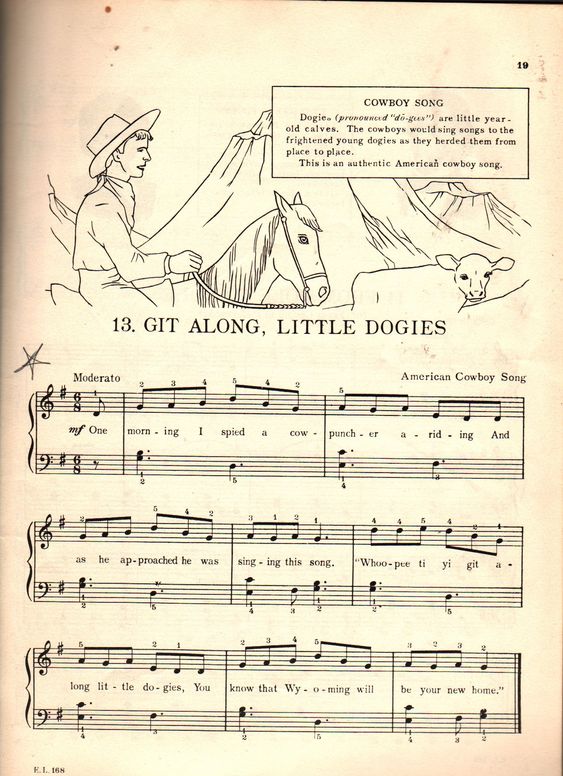

I began piano lessons at the age of six in Chattanooga. My teacher was a man I suspect to have been in his thirties but who seemed old to me. He taught from the John W. Schaum Piano Course, which comprised a series of graded books, each assigned a letter of the alphabet and each with a distinctively colored cover with a pointillistic image of a grand piano in the center. There was the Red Book (A), Blue Book (B), Purple Book (C), and so forth, the colors bearing no relationship to the letter. Over the course of my ten years as a piano student, I made it up to the Brown Book (F), two books shy of the last book, the Grey Book (H). The Schaum course is still sold, although piano pedagogy has made great strides since the first publication of the course in 1945. My strongest memories are of the first book, the Red Book (A), which established a pattern continued in subsequent volumes: short selections—often folksongs or clumsily composed technical exercises—illustrated with crudely drawn pen-and-ink drawings that looked like a child’s outline tracings. They appeared on the top third of the page in the Red Book and took up less real estate on the page as the series progressed. Many of these drawings were alarming to me—because the drawings were either frightening (for a tarantella, I was treated to the image of a girl dancing herself to death), bizarre (for example, this illustration of a “kangarooster”, or simply bad (such as this illustration for “Git Along Little Doggies”).

“Git Along, Little Dogies” from the Purple Book

The Red Book opened with “The Woodchuck” and “Snug as a Bug in a Rug.” All the selections had words, possibly as a mnemonic device or to give the teacher something to sing while the student fumbled.

My piano lessons were in the afternoon, after school. My mother drove me to the piano teacher’s home, a ten-minute drive from our house, on the other side of Ringgold Road. My teacher was a timid, mousy man with great patience. He taught in a dim room, and the light of the piano lamp bouncing off the white pages of music illuminated our faces. The lesson I remember best was the Friday in November 1963 when Kennedy was shot. My mother had the radio on during the drive to the piano lesson, and my teacher took me in for my lesson as usual. He asked me to play that week’s assignment (I imagine by that point I was in the Blue Book), and once I began, he moved to an adjoining room, where he stood in front of a small black-and-white television to watch the coverage. I played through the assignment then sat idly once I’d finished. I had just turned seven and was old enough to know who President Kennedy was, but the shock of what had happened was lost on me until several years later. What I did understand was that this event was important enough that it took my teacher away from my lesson. Later that day, I saw people on the television crying.

Move to Morristown

%%

My father was an organic chemist, and when we lived in Chattanooga in the early 1960s, he worked for Tennessee Products, a tar and coal company whose industrial site, just west of downtown Chattanooga, was declared a contaminated Superfund site from 1995 to 2019. In 1963, he got a job offer from Chemetron Chemicals to work at the Rock Hill Laboratory in Newport, Tennessee, where he remained for the rest of his career. The lab was a small facility that did research and development on products that were manufactured at Chemetron’s plant in a nearby industrial park. The laboratory changed hands from Chemetron to Arapahoe Chemicals (a division of the Syntex Corporation) in 1974, and he continued working in the lab until he retired in 1982, when Syntex closed the lab. It remained idle until 1987, when the notorious Flura Corporation purchased it for the manufacture of halogenated gases, including gases used in chemical warfare, and in 1999, a tank leak led the EPA to declare the lab a Superfund site.

Newport is in the heart of east Tennessee, about thirty miles east of Knoxville and a two-and-a-half-hour drive from Chattanooga. I was already familiar with the drive from Chattanooga to Knoxville from our occasional trips to see my mother’s parents in Talbott, a village thirty-four miles northeast of Knoxville. Not far out of Chattanooga, we passed the Bowater newsprint plant in Calhoun, Tennessee, an hour northeast of Chattnooga, which was enveloped in smoke and spread the stench of rotten eggs throughout the region.

When my father took the job in Newport, for the first year he traveled to East Tennessee on Sunday night, spent the week working, and drove back to Chattanooga on Friday night. A relative of my mother’s, Mary Kate Hale, put him up in a room in her sprawling Queen Anne home in Morristown, a thirty-minute drive north of Newport.

My parents began planning to move the family. This would be a change from the life they had known in Chattanooga, the fourth largest city in Tennessee. Newport was a small country town situated on the Pigeon River in Cocke County, which, since the 1920s, had been notorious as the center of a rural moonshine network, backed by corrupt law enforcement. It was also a hotbed for gambling, cockfighting, and prostitution. I imagine after my father had driven a back and forth through the town a couple of times, he decided it was no place to raise a family. Knoxville was the closest large city and would have been an ideal location for a young family, but living there would have required an hour commute in the morning and evening. My father was living in Ms. Hale’s house in Morristown, a small city with a thriving furniture industry and reasonably good schools, and moving the family there seemed the best solution. It was also eleven miles northeast of Talbott, where my mother was born and her father and stepmother still lived.

This was a time of growth for Morristown, and subdivisions were being developed on the east and west ends of the city, strewn along highway 11E, an arterial road that led from Jefferson City to the west, ran through the heart of downtown, and then extended beyond the city to the east, where it connected with US-11W and Kingsport. They decided to build a house in a new subdivision on the east side of Morristown. In the afternoons, my father would drive home to Mary Kate’s house and then after dinner visit the construction site a mile away on Hugh Drive and take photographs and home movies of the house as it was being built. (He later edited his film footage together into a montage proceeding from groundbreaking to completion, and created title boards using a feltboard and cut-out letters.

Indian head hood ornament from a 1950s Pontaic