Richard Johnson and the Indiana University Percussion Department: A Personal History

When I entered the University of Tennessee in 1974, my career goal was to become a public-school band director, and if I’d completed a bachelor’s degree program in music education as planned, I would have had the credentials I needed. Instead, I was drawn into the study of musicology—something I’d been thirsting for without knowing it—and left with a bachelor’s degree in music history that offered no prospects for employment. That didn’t matter to me, since I enjoyed student life. During my senior year at UT, I told my high-school girlfriend that I’d be happy spending the rest of my life at UT, living in a dormitory and taking classes for $3,000 a semester. (I didn’t think through where that money might come from.) With a bachelor’s degree in music history, I was on a path where I needed to be in school for at least seven more years if I were ever going to be employed. It would require advanced degrees, first the master’s, then the doctorate.

Where to go to graduate school? One option was to stay at the University of Tennessee, but I could see how limiting that would be. Although the school offered advanced degrees in musicology, it wasn’t a strong program. The faculty were knowledgeable, but they published no research and weren’t active in the profession. A stronger prospect was the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, a five-hour drive away, which had a distinguished program in musicology, led by faculty who were widely published. Norris Dryer, my boss at WUOT-FM, lobbied hard for Indiana University, where he had graduated in the 1960s. He believed that IU, with it’s conservatory-quality School of Music—the largest in the United States at that time—had a lot to offer a musicology student with an interest in performing. I remember applying to Chapel Hill, Indiana, and perhaps one other school. Chapel Hill turned me down, but Indiana admitted me and offered a tuition stipend for the first year. My choice had been made.

When I traveled the five hours northwest to Bloomington to start my graduate studies at IU, I began my life outside the South. Before moving to Indiana, I had spent all my life in East Tennessee, and to my mind, anyplace above Kentucky was the North. One in Bloomington, I felt as if I had crossed the border into Yankeeland. Several months later, when I explained this feeling to friends I had made in Bloomington—including people from Canada and Vermont—they laughed. For them, Bloomington was a tiny Southern backwoods town. In many ways it was. When I return there, I see elements of Southern life and manners among the people of Bloomington who aren’t affiliated with the university—which shouldn’t be surprising, since it is only a two-hour drive from Louisville.

I had applied to IU as a musicology major, but I was interested in continuing to play percussion and to get a minor in performance, which meant enrolling in private lessons and performing in an ensemble. Norris had mentioned that IU had five orchestras, and any one of the five would be better than the Knoxville Symphony.

In the days before the internet, information for incoming students was delivered in the mail, and I had received a packet for new students at home during the summer. Once I had settled into Eigenmann Hall, the graduate-student dormitory in the northeast corner of campus, I sat down with a campus map and found the Music Annex, where I would be auditioning before the percussion faculty. The building was famous for being an architectural oddity. A tall, round structure made of Indiana limestone, almost industrial in appearance, it contained most of the school’s teaching studios, practice rooms, and small rehearsal spaces. I found a signup sheet for auditions in the percussion department on the fourth floor, and I signed up.

While at the University of Tennessee, I had played in a small percussion group organized by Michael Combs, the percussion professor, to perform one-off concerts at local schools and retirement homes. We were paid by the Music Performance Trust Fund, which had been established in 1948 through an agreement between the musicians’ union and the recording industry to provide free performances of live music. For these concerts, we played light classical music and popular songs in transcriptions by Mr. Combs for two marimbas, vibraphone, drum set, and double bass.

Whenever Mr. Combs scheduled one of these concerts, he reserved a university van, and we students handled the loading and set up at the venue. We could squeeze the two marimbas and vibraphone into the van by loading the marimbas long end first, then carefully sliding the vibraphone, narrow end first, into the wedge of space separating the marimbas. None of us found it unusual that we were using a university vehicle for our own purposes. The dividing line between university activities and extracurricular activities was often blurred. For example, the percussion instruments we used for Knoxville Symphony performances were the property of the university, which had no official connection to the orchestra, although many of its players were on the faculty.

Through these Trust Fund performances, we earned a bit of spending money. It wasn’t much, but for a student musician, the small checks were good pay for only a few hours of work. We never played more than an hour; we usually spent more time loading and traveling than playing. Once we had learned the repertory, we rarely reeded to rehearse. This also meant we often played difficult keyboard mallet parts cold after not seeing them for several weeks. Over time, I adapted and learned to sightread moderately difficult marimba parts with only a few mistakes.

During the audition at IU, this experience paid off. At the scheduled time, I knocked on the large door of a rehearsal room on the fourth floor, and a few seconds later, the door opened, revealing a short Black man, who welcomed me with a broad smile and shallow bow and introduced himself in a light voice. With a wave of his arm, he ushered me into the large room and directed me to the snare drum, timpani, and marimba assembled at its center. He introduced the two other men on the auditioning committee, who were sitting across the room behind a long table.

One was William Roberts, principal percussionist of the Denver Symphony Orchestra, who had been brought in as a visiting instructor to cover for the sabbatical leave of the chair of the percussion department, George Gaber (1916–2007). Gaber had joined the faculty at Indiana in 1960 after twenty years of freelancing with orchestras and broadcast companies in New York City, and he had built a strong program at IU. Students came to Indiana to study with Gaber. Although Roberts was an excellent percussionist and a good teacher, Gaber was such a strong force in the department that he remained a presence even in his absence; he continued to haunt the halls and rehearsal rooms of the percussion department.

The other was Wilber T. England, a no-nonsense assistant director of bands who coached the drumline of IU’s Marching Hundred. I don’t remember anyone studying with England, and since I wasn’t in the band, I rarely encountered him after my audition.

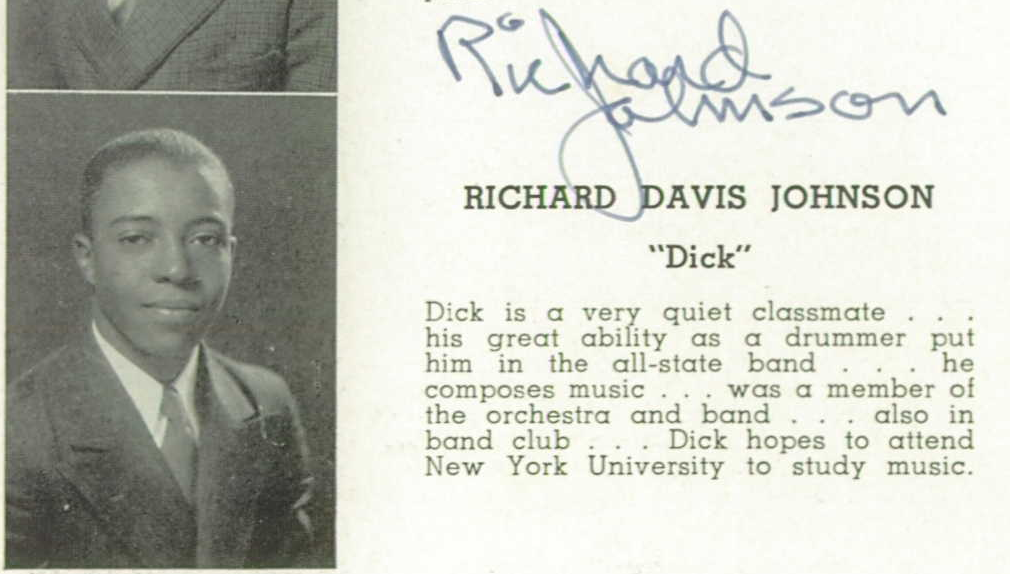

And the courtly man who had opened the door was Richard Davis Johnson (1921–83), associate professor of music at IU and its first instructor of percussion. He had come to Indiana University as a student in 1946, presumably on the GI Bill, following his service in the US Air Force from 1943 to 19461. (He was commissioned second lieutenant at the Navigation School at the Hondo (Tex.) Air Field in April 1945.) At IU, he initially studied modern languages but switched his major to music, which had been an interest of his since the sixth grade. His senior-year high school yearbook says that “his great ability as a drummer put him in the all-state band,” and he “was a member of the orchestra and band” and “hopes to attend New York University to study music.”

Johnson grew up in Plainfield, New Jersey, the fourth of six children2 of George W. Johnson (1885–1963) and Clara Banks Johnson (?1896–1943), both of whom were born in Virginia and moved to New Jersey around 1910. George was a custodian at the Plainfield City Hall for twenty years.3 Their oldest child, Gladys, was born ca. 1906, and the youngest, Grace, was born ca. 1927. In 1940, when Richard was 18 and graduating high school, two of his older siblings were still living at their home at 1239 Columbia Ave.: Gladys, 25, was a servant in a private home, and James, 22, was a railroad porter.4 According to Johnson’s 1941 draft card, his mother worked for New Jersey Bell Telephone in Plainfield.5 She died two years later,3 possibly after Johnson had begun his military service.

In high school, Johnson aspired to attend college at NYU, which seems a reasonable yet ambitious goal for a New Jersey student, and it’s possible he did this, since there is no record of his activities during the two or three years between his high school graduation and his enlistment in the US Air Force. Still, there is no mention of study at NYU in his obituary or in any contemporaneous documents. His post-high-school education apparently began in 1946 after he left the US Air Force, and one of many unanswered questions about Johnson’s life is why he ended up in Bloomington, Indiana, rather than returning to the East Coast.

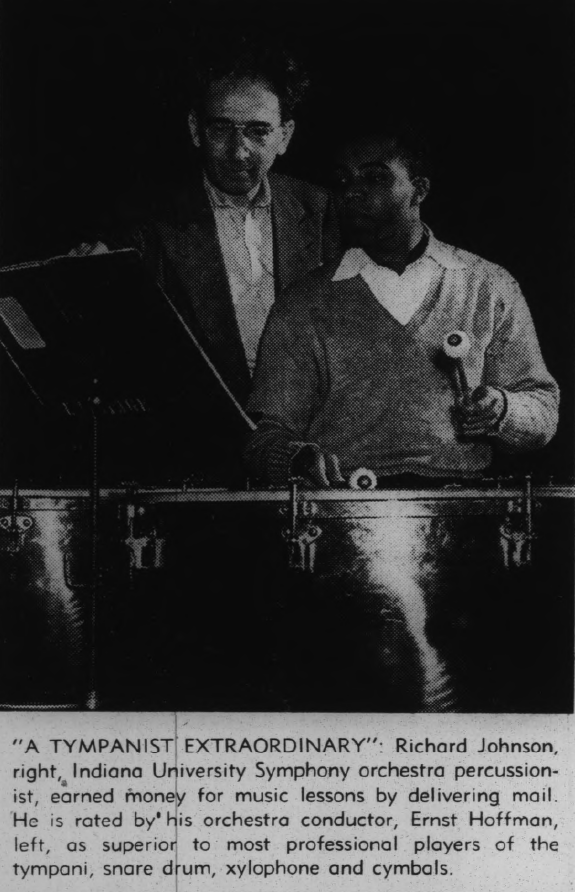

Whatever the reason, Johnson ended up at Indiana University, and after four years, he had established himself as a talented percussionist. It’s not clear with whom, if anyone, he studied with during these years, but he made extraordinary efforts to get the training he needed, even when it meant leaving Bloomington. According to a 1950 newspaper article, for three summers (probably 1947–49), Johnson hitchhiked home to Plainfield and worked as a mail carrier to raise money for lessons at the Juilliard School with Saul Goodman (1907–96), timpanist of the New York Philharmonic.6 Johnson had a strong supporter in Ernest Hoffman (1899–1956), former conductor of the Houston Symphony, who had joined the faculty of Indiana University in 1947 as director of orchestral music. In the 1950 article, Hoffman said that “I felt he was superior to any percussion player that ever played under me either in this country or among the leading orchestras in Germany.”6

According to Johnson’s obituary,1 in addition to his work with Saul Goodman in New York, he studied at some point at McGill University in Montreal, but it’s not clear whether this was during his undergraduate years or after graduation—or whom he studied with.

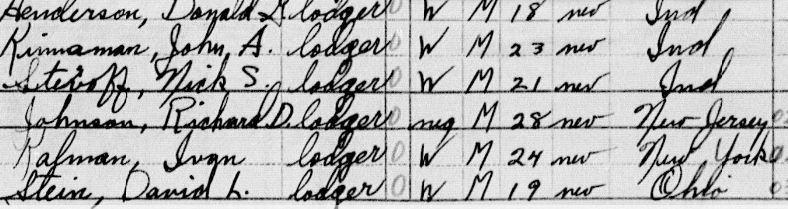

Even before he graduated from IU in June 1950, he had taken on responsibilities in the School of Music, serving from 1948 to 1950 as “undergraduate assistant in percussion” for the school.1 The 1950 US Census lists his profession as “assistant in music” at the university and reports that he was a lodger in North Hall (now part of the Collins Living-Learning Center) on North Woodlawn at 10th Street.7

The 1950 article in the Indianapolis Record says that “one of Johnson’s ambitions is to go to Paris and for a short time work with percussion players of the Orchestre Nationale which played at Indiana University last year under the direction of Charles Munch.”6 After graduation, he traveled to France to study with Felix Passerone, timpanist with the Paris Opera Orchestra, “who was a professor of percussion at the Paris Conservatoire from 1947 to 1957. Passerone strove to bring percussion into the spotlight of Parisian society, and trained his students to do the same.”8 His choice to study in Paris after graduating might also have been related to his race. Paris had been a safe haven for Black Americans since the 1920s and 1930s, and following World War II there was an influx of Blacks, including prominent American writers and jazz musicians.

Johnson returned to the US from Europe by ship. On 18 August 1951, the SS Edam, operated by the Holland America Line, arrived in New York City from Antwerp, Belgium, and among the passengers was twenty-nine-year-old Richard D. Johnson. The ship manifest lists him having the address of 1475 McCrae Place in Plainfield, and his baggage consisted of “3 suitcases, 1 trunk, 1 case.” After landing in New York, he probably spent some time with his family in Plainfield before traveling back to Bloomington for the start of fall classes on September 26.

Beginning with the fall 1951 semester, Johnson began teaching percussion at IU. Although he was an accomplished and talented percussionist, he joined the IU faculty without first having established a professional career as a performer. Some researchers have speculated that he wasn’t able to secure a position in a US orchestra because of racism, but given the compressed timeline of his military service (1943–46), undergraduate studies (1946–50), time in Paris (1950-51), and appointment at IU (1951), there would have been little or no time for auditions, failed or otherwise. It’s possible he was satisfied with the prospect of teaching percussion at a prominent university—or perhaps had no desire to live the life of an orchestral musician, knowing what that life would be like for a Black man in the 1950s.

The 1956 Bloomington city directory lists his address as the “Campus Club,” but the directory for the following year lists his address as an apartment at 1415 East Third Street, and the name of a wife, Alice, appears in parentheses after his name. (Because this address corresponds to the address of the School of Music, it’s possible this was simply an office mailing address.) In 1958, he was promoted to the rank of assistant professor, and the directory shows that he and Alice had moved to an apartment at 10 Lingelbach Lane, northeast of campus.

Ten years later, in 1968, Johnson was promoted to associate professor with tenure. He was never promoted to full professor. According to a 2019 Facebook posting from the Percussive Arts Diversity Alliance, he was the first Black percussion professor in the US and the first tenured Black professor at Indiana University.

When I was at IU, no one mentioned Johnson’s historic place in the university, and he was not one for self-promotion. In public, he was polite but reserved—dapper in appearance, with close-cropped hair, a neatly trimmed mustache, and heavy black-rimmed glasses. He smoked a pipe. Most of his time was spent in his teaching studio, and we occasionally heard the sound of him practicing timpani through the heavy door. He smoked his pipe. Whenever he interacted with students, teaching in his studio or chatting in the hallway, his somber affect disappeared, and he was ebullient and charming. As a teacher, he was encouraging, yet careful to correct problems with technique. He was never chiding, dismissive, or angry, unlike other teachers in the school. (A memorial resolution passed by the IU Faculty Council in 1985 describes him as “a quiet, modest, unassuming, cultured man who loved good books, fine music, great art, and world travel.”)

In the School of Music, students were defined by whom they studied with. Because Gaber was seen as the star of the percussion faculty, students wanted to be selected for study his studio. Although Johnson had been at IU nearly ten years longer, studying with him unfortunately implied that you were not among the best.

In my audition for the percussion faculty that first week, I did passably well with the snare drum and timpani excerpts, but when asked to sight read a passage with running sixteenth notes on the marimba, I excelled, thanks to my years of playing marimba parts with little rehearsal for the Trust Fund group at UT. As I hit the bars, I heard a murmur among the percussion instructors that seemed affirmative.

One purpose of the audition was to determine whom I would be studying with. There was little question about this. As a percussion minor, I would be studying with Mr. Johnson, and I started my lessons the following week. After the first few, I realized his standards were higher than Michael Combs’s. He quickly homed in on flaws in my playing that Combs—himself not a precise player—had missed. Mr. Johnson’s expertise was with timpani, and although I remember working on some keyboard mallet excerpts in his studio, most of the playing during lessons was on a set of four timpani in the corner. One memorable lesson focused on the timpani solo that opens the last movement of Mahler’s Seventh Symphony, which he had me play to the accompaniment of an LP recording. Because the timpani started the movement and there was no aural cue on the recording, each time Mr. Johnson dropped the needle, I had to jump at the first sound of the drums and then catch up to the beat.

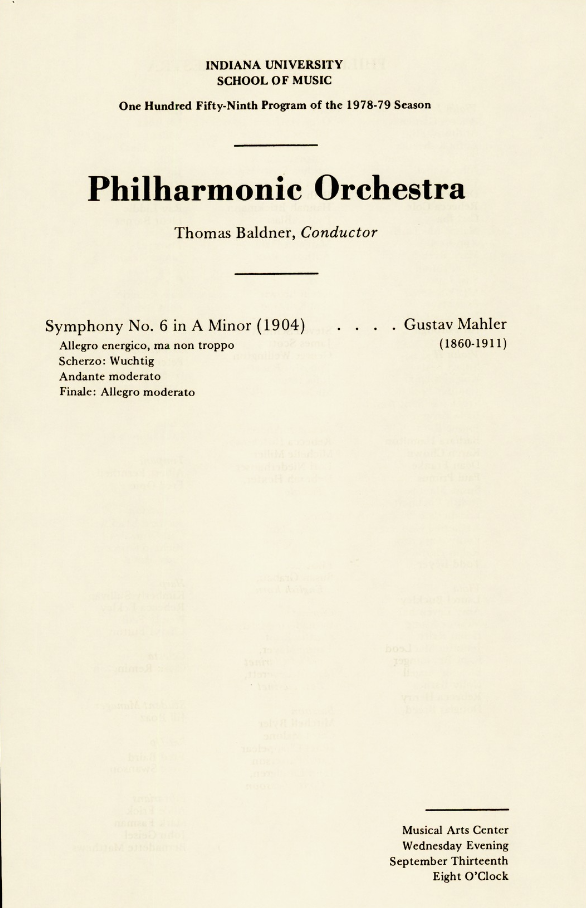

The second purpose of the audition was to determine where I would be placed among the five orchestras and the concert band, each of which had four or five available percussion positions, depending on the repertory being played. When the audition results were posted, I had ended up in the Philharmonic—the top orchestra. I didn’t realize how unusual this assignment was until I got to know a few percussion majors and sensed the surprise and resentment that a percussion minor with no intention of becoming a professional had got into the Philharmonic.

Although I never heard it from anyone in a position to know the truth, rumor had it that most of the percussion assignments in the top orchestras went to Gaber students (not a surprise, since he attracted the best students), but Johnson was allowed to place students in one or two slots in each orchestra. I have always assumed this was how I ended up in the Philharmonic. Gaber’s absence might also have played a part. This was Roberts’s first semester auditioning students, and it’s possible he deferred to Johnson, with his decades of experience at IU.

A few days after the audition, classes started, and I began rehearsing with the IU Philarmonic—the best orchestra I would every play in—twice a week in preparation for a performance the following month of Mahler’s Symphony no. 6. I believe the timpanist, Fred Opie, a graduate student who studied with Gaber, served as principal for the percussion section and made the part assignments. I ended up with the keyboard mallet parts (including exposed xylophone and bell parts in the first and second movements), and in the last movement, I played one of the most outrageous percussion parts in the orchestral repertory, the Hammerschlag (hammer blow), which we executed using a wooden mallet with a head six inches in diameter that I raised over my shoulders and landed with a heavy thunk against a cello podium9 resting on a couple of chairs.

The performance was on 13 September 1978, and with the semester starting on August 28, we had no more than six rehearsals over two and a half weeks to prepare the symphony. From the first downbeat, it was clear this was no ordinary student orchestra. The strings sounded as if they were one instrument, with none of the unfocused noise of swarming insects that I’d grown used to in the Knoxville Symphony. Brass tones were round and bell-like, and there was rarely a clammy splat. This allowed the conductor, Thomas Baldner, to spend most of his time refining the ensemble’s sound and molding his interpretation of this great work. Baldner (1928–2015) was a German-born conductor who emigrated to the US when Hitler came to power. Before joining the faculty of IU, he had founded the Greenwich (Conn.) Philharmonia and been artistic director of the Rheinisches Kammerorchestra in Cologne in the 1950s. He was a soft-spoken conductor who never raised his voice, but that didn’t mean he was never angered. Whenever he stopped the orchestra to adjust the phrasing or tuning of a section, if the problem hadn’t been fixed by the second attempt, he would tilt his head forward, peer at the offending players through his eyebrows, and whisper, “Again,” and with an ever-shrinking beat pattern, repeat the passage.

I played six programs that first year with the IU Philharmonic:

- 13 Sep 1978 (program #159 of the 1978–79 season): Mahler 6th (cond. Thomas Baldner; xylophone, orchestra bells, hammer)

- 18 Oct 1978 (#232): Daphnis et Chloé Suite no. 2 by Maurice Ravel (cond. Margaret Hilis; tambourine)

- 24 Jan 1979 (#427): Stille und Umkehr by Bernd Alois Zimmermann (cond. Thomas Baldner)

- 14 Feb 1979 (#468): Die Walkűre, act 1 (cond. Keith Brown; second timpani)

- May–April 1978 (#580): Boris Godunov (cond. Baldner)

- 18 Apr 1979 (#807): Three Pieces for Orchestra, op. 6, by Alban Berg (cond. Bryan Balkwill)

The Daphnis et Chloé performance was memorable because Mr. Gaber was in the audience. After weeks of hearing about him and seeing how his presence was felt in nearly everything his students did during rehearsals, I was told he would setting aside whatever activity was filling his leave of absence to attend our concert. As we set up our percussion instruments on the stage on the evening of the event, I was told he was “up there, in the balcony.” I squinted to look for him beyond the stage spotlights, but, never having met him, I couldn’t figure out which dark figure he might be, and he remained a phantom. Once we had set up, I started warming up on the tambourine to find out how my thumb rolls were landing. Judy Moonert, a third-year undergraduate major, rushed across the stage to me. “Mr. Gaber doesn’t like us warming up on stage before a concert.” I put placed the tambourine on a trap table and sat down.

The concert went well. Daphnis et Chloé has a tricky tambourine part involving shaking, whacking, and skittering the thumb across the head of the instrument. The performance came off as well as it could have. Afterwards, as we were packing up, I saw the other percussionists move toward the timpani. I looked over and saw that a man I assumed to be Mr. Gaber had come onstage to greet the players, nearly all of whom were his students. I joined the circle. There was spirited talk from the students and a few words from Gaber, who commented on the playing of each student. At one point, he turned to me and said, “Nice tambourine playing.” The others looked at me. I returned their gaze and felt I could now be accepted.

The 10 April 1979 concert that included the Berg op. 6 was an installment in a years-long series of concerts conducted by Bryan Balkwill (1922–2007) that surveyed the major orchestral works of the Second Viennese School. Coincidentally, the Berg op. 6 was the second major orchestral work, besides the Mahler 6, that included the hammer, but this time it was handled by another student.

The following year, Balkwill programmed the Schoenberg Piano Concerto as part of this series. As with any concerto performed by one of the orchestras, there was an open audition among the students to determine who would be the soloist. The concerto is a difficult work—to play, to understand, and for some, to listen to—and although everyone expected only a handful of students to turn out for the audition, no one suspected there would be only one student vying for the slot or that the pianist would end up being James Irsay (1947–2024), host of “Music for Piano” on WFIU-FM on Monday nights.

Irsay’s radio program always opened with a scratchy 78-rpm recording of “Spinning Song” by Felix Mendelssohn, performed by a variety of pianists of the 78-rpm era—Ignaz Friedman, for example, or Josef Hoffman. After the two-minute “Spinning Song,” Irsay would welcome listeners to “Muzak for the Keyboard” (as he nearly always twisted it) and then take off in any number of directions. Once he talked for fifteen minutes about his recent visit to Afghanistan and how he saw dogs fight viciously over the spoils below a wooden outhouse. He did comic bits: a prerecorded radio drama about Schumann’s courtship of Clara Wieck featuring an over-the-top portrayal of Clara’s domineering father. A “Music for Dogs” segment featured imagined canine composers (including Leslie Bassethound and IU composers St. Bernhard Heiden and Frederick Foxhound.)

At this point in his career, Irsay was a graduate student studying music composition. Although he was known locally as an expert on early recorded pianists and their interpretations, he rarely performed, making the Schoenberg performance intriguing on a number of levels: it was a chance to hear a rarely programmed work performed by an eccentric nonmajor pianist of unknown skill. I was in the audience for the concert, and Irsay played with the confidence and control of a professional—a jawdropping, nearly flawless, performance.

All programs at IU were recorded, and Irsay’s performance of the Schoenberg Concerto has been uploaded to YouTube. After leaving Bloomington, Irsay lived in New York, and for many years hosted the program “Morning Irsay” on WBAI-FM.

My ensemble assignments during my second year were not nearly as appealing as they had been that first year. One semester I was in the wind ensemble, and the other I played in one of the lower orchestras—but I played timpani rather than percussion. The highlight of my second year was playing timpani in Tchaikovsky’s Symphony no. 4.

During my three years at Indiana, I didn’t have a car, and the only way I could travel home was by finding a driver through the “ride board” in the student center. A tackboard displayed cards filled out by students who were driving somewhere and willing to take on a passenger in return for gas. My first year in Bloomington, I used the ride board to get to Knoxville for Thanksgiving to see the woman I had dated during my last year at the University of Tennessee (and whom I later married). That trip was a disappointment, and it would be the last time I returned to Tennessee from Bloomington during the school year.

For this second year I was invited to Thanksgiving dinner by Don Hirose, an undergraduate percussion major from Hawaii who was a student of Mr. Johnson’s. My girlfriend at the time, Nancy B—, was a citizen of Canada, where Thanksgiving is celebrated in October, and because she planned to stay in Bloomington, Don invited her too. (I believe, besides knowing Nancy as my girlfriend, he had taken a music history survey class for which she had been the teaching assistant.)

Don was a lively guy, and like most of the other percussionists in the department, he had met me while hanging out on the window sill of the fourth-floor elevator lobby, where percussion students would congregate randomly whenever we needed a break from practicing. When Don and I were talking on the sill one day, he told me about coming to the mainland US for a music camp when he was in high school. He was the only Pacific Islander at camp and was picked on constantly. The taunting kids assumed he was Japanese. “One afternoon, three of them ran by my dorm room and shouted, ‘Remember Pearl Harbor!,’ and I thought, you dumbasses, we were the ones being attacked!”

A few days after Don had extended the Thanksgiving invitation, he told me he had an idea.

“I was thinking of inviting Mr. Johnson,” he said.

I couldn’t imagine inviting a professor to Thanksgiving dinner. “Really? Do you think he’d come?” I said.

He shrugged. “I don’t know. Can’t hurt to ask. Think about it. He’s alone. Has no family. He’d probably appreciate the invitation.” It was bold, but thoughtful—just the kind of thing that Don would come up with.

Mr. Johnson spent most of his time on campus in his studio, and presumably the rest of his time was spent at home. He never talked with students about his life outside the school. I saw him at percussion recitals, opera performances, and the occasional orchestra concert, but I never saw him around town.

When Don asked Mr. Johnson, he said yes. We all gathered in Don’s apartment for an odd but festive Thanksgiving. Don prepared a turkey. Nancy, an excellent cook, brought a dish. I can’t remember who was there, other than the four of us, but I suspect there were at least two other students. Mr. Johnson was in high spirits. After a few drinks, we all loosened up, and when Don let a “fuck” or two slip, Mr. Johnson laughed and exclaimed, “Oh my,” then jokingly raised his hands to his ears.

During my third year at IU I had to focus my time on coursework to complete my library science degree, and I drifted away from the percussion department. I no longer performed with one of the orchestras, and I didn’t study with Mr. Johnson. In summer 1981, I graduated and a few weeks later moved to Evanston, Illinois, to catalog music at Northwestern University. Nancy stayed in Bloomington and worked in the music program office while she finished her doctorate.

In 1983, I got a call from Nancy. Mr. Johnson had committed suicide. She didn’t know much more about the circumstances than what she had read in the paper—that it had happened at the student union. He was sixty-one.

On Ancestry.com I recently found the coroner’s report, which lists the place of death as his residence, a room in the Biddle Hotel and Conference Center of the Indiana Memorial Union. Although the hotel was part of the building complex that served as the university’s student center, it did not house students. The hotel was built in 1960 to “foster personal and professional growth through conferences, workshops, and seminars.”10 When I was a student, I knew of no one who lived in the hotel, and I imagine Johnson’s living arrangement had wasn’t common. Possibly, it was unique. He died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head, but the coroner also noted under “other significant conditions” a gunshot wound to the chest, presumably also self-inflected.

I thought—and continue to think—a lot about Richard Johnson’s life and death and how isolated and lonely he must have been. When I was his student, his solitude had seemed nothing more than an idiosyncrasy of a man who valued his privacy. He was quiet and kept to himself—never spoke of family, living or dead—but it didn’t seem more than that. On the other hand, although he would be unfailingly cheerful and charming when talking with others, occasionally the mask fell there was a touch of sadness about him and a weariness in his eyes.

Many questions that arise from the coroner’s report remain unanswered. One would expect a tenured professor who had been a member of the faculty for decades to be living in a house or an apartment and not in a room in the Union, and one wonders how long he had been there. The report lists as the “informant” Earl C. Johnson, an older brother, who lived in Nashville. Had they been in touch before his death? Missing from the coroner’s report but mentioned in his obituary1 is a daughter, Allegra, presumably the child of Johnson and Alice, the woman listed in his entry in the 1957 Bloomington city directory. His marital status in the coroner’s report is “divorced,” but there is no public record of a marriage or divorce to be found in Ancestry.com.

Finally, there is the larger, darker question of what might have led him to take his life. Perhaps he was despondent over his marginalized role in the School of Music and his lack of recognition. But these were slights and insults he had already endured for decades. Perhaps there were problems or conflicts with friends or family members. Perhaps his health was in decline. In any case, the question at the center of his sad demise isn’t to be answered by online documents and newspaper articles, and now that over forty years have passed, an answer is not likely to come from his survivors. It was a tragic end to a quiet, dignified life of great accomplishment, and the story behind it have to remain a mystery.

January 2025 update: In September 2024, I received an email from a former student of Richard Johnson’s. She had read my posting on Johnson and had a few things to add. When she was a student in the late 1960s (about a decade before me), Johnson lived in a house in rural Brown County, east of Bloomington. A few of the students in the department visited him occasionally. She said he was harassed by neighbors while living in Brown County, and it became such a problem that he moved back to Bloomington, into the Union. After graduating in 1971, she moved to New York City for a couple of years, then returned to Bloomington in 1973–76 to work on an MBA degree and had a job with the Union Board. Johnson would run into her occasionally in the Union, and one day he appeared in her office. He needed her help. He was pursuing a promotion to full professor and asked whether she would write a letter in support of his teaching—which she did. He was denied the promotion. She also mentioned that Johnson wrote a percussion methods book, and she served as a hand model for some of the photographs. (I haven’t been able to find evidence that this book was published—at least there are no holdings in OCLC’s Worldcat.)

“Richard Johnson, Music Professor,” Indianapolis News, 1 September 1983, 42 (see reproduction in this post). ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1930. Census Place: Plainfield, Union, New Jersey; Page: 12A; Enumeration District: 0109; FHL microfilm: 2341123. ↩

“George W. Johnson, Ex-City Hall Custodian,” Plainfield (N.J.) Courier-News, 5 February 1963, 8. ↩ ↩2

United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1940. Census Place: Plainfield, Union, New Jersey; Roll: m-t0627-02387; Page: 2A; Enumeration District: 20-64. ↩

National Archives, St. Louis, Missouri; WWII Draft Registration Cards for New Jersey, 10/16/1940–03/31/1947; Record Group: Records of the Selective Service System, 147; Box: 325. Ancestry.com. U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940–1947. Lehi, UT: Ancestry.com Operations, 2011. ↩

“I.U. Tympanist (Drummer) in Orchestra Rated as Tops,” Indianapolis Record, 18 February 1950, 9. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Seventeenth Census of the United States, 1950. Census Place: Bloomington, Monroe County, Indiana; Enumeration District 53-11A, sheet 24, line 28. ↩

Mike Truesdell, “Bringing Percussion into the Spotlight of Society,” Juilliard Journal, November 2013. https://journal.juilliard.edu/journal/1311/bringing-percussion-spotlight ↩

A wooden platform, roughly four to ten inches high, used by cellists—particularly soloists—to amplify the sound of the instrument and increase their visibility. ↩