Norris Dryer and WUOT-FM: A Personal History

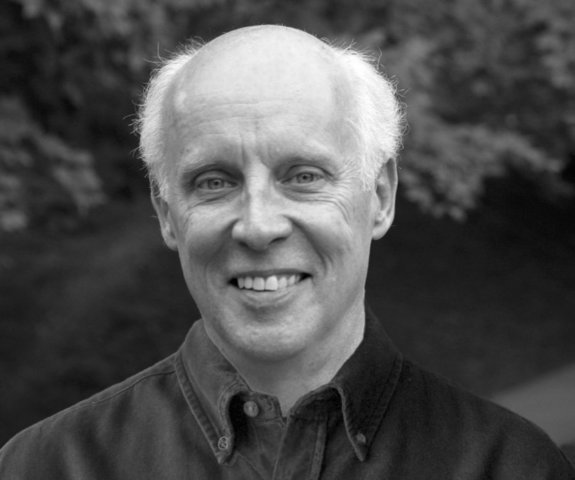

Norris Dryer, in an undated photo (photo credit: Norris Dryer)

“How can you spend all this time sitting here when you could be home improving your mind?” The question didn’t sound outlandish when I asked it, but nearly a half century later, it’s embarrassingly comical. I posed it to Norris Dryer at a night game of the Knoxville White Sox in 1977, when the minor-league baseball team played in Bill Meyer Stadium, just north of downtown, nestled in a bend of Interstate 40.

Norris was a devoted fan of the Knox Sox. He attended every game that wasn’t scheduled against a rehearsal of the Knoxville Symphony Orchestra (KSO) or the Monday-night program he hosted on WUOT-FM. Given how many games he attended each year, he would have saved money by buying a season ticket, and earlier in the evening, as he opened his wallet to buy our tickets, I asked him why he hadn’t done that. “I agree that would make sense to most people, but I look at it a different way. I want to support the team, and I put more money into the team by buying single tickets.”

Bill Meyer Stadium (photo credit: Eric and Wendy Pastore)

It was my first time attending a professional baseball game, and although I had played softball in phys ed classes in grade school, I had a paltry understanding of the game. As we watched, I asked questions about the interaction between the pitcher, catcher, and batter. I wondered why a base runner could plow through first base without being tagged out but not second base. Why wasn’t a ball that rolled out of bounds foul? An hour into the game, I started running out of questions. “How long do games last?” “About two and a half hours. Usually never less than two hours and rarely more than three.” “And you stay for all of it?” “Yes.” We watched silently, and as the time passed, I felt restless. I heard light chatter from the crowd that seemed to reflect their interest and, at times, excitement, but it was lost on me. There were long pauses between the pitches across the plate. The pace felt glacial, and it made me uncomfortable. “How can you spend all this time sitting here when you could be home improving your mind?” It was a serious question. I don’t remember how Norris answered. I suspect he laughed.

But he certainly remembered the question. He reminded me of it when we met again many years later, after I’d left Knoxville, and I suspect he had repeated the story to many of his friends during the intervening decades. I realize now how funny the question must have seemed—how much of its humor lay in how reasonable it was to question spending nearly a fifth of one’s waking hours in an idle pursuit. At the same time, it was ridiculous question, since most people spend at least that much time doing something recreational and enjoyable—sitting at a bar, listening to the radio, gardening. Why not watching baseball?

During the time I knew Norris—from my years at the University of Tennessee in the late 1970s until our last meeting in 2003—he drove a lemon-yellow Volkswagen Thing. It resembled a jeep and in fact was a military vehicle, the Volkswagen 181, repurposed for civilian use. The windshield could be folded forward, flat against the hood, and there was a convertible roof but no overhead rollbar, so if the car flipped over, the passengers would likely be crushed. The sheet-metal interior was painted the same glossy yellow as the exterior, the seats were black vinyl, and there were perforated rubber mats on the floor. Volkswagen introduced the Thing in the United States in 1972 and dropped it in 1975 because it failed to meet new safety standards—not because of the absence of a rollbar but because there was insufficient distance between the driver’s head and the windshield.

Norris Dryer, late in his life, with his Volkswagen Thing (photo credit: Knoxville Symphony Orchestra blog)

There were few Things in East Tennessee, and Norris’s was almost certainly the only yellow one. It was a quirky choice, and the car always drew comments. Perhaps Norris liked it because it worked against various stereotypes. He played in the first-violin section of the Knoxville Symphony Orchestra for several decades and was often asked (or volunteered) to shuttle guest artists from their hotel to the concert hall for the orchestra, the Knoxville Civic Auditorium, a 2,500-seat theater in the Knoxville Civic Colesium. A young Joshua Bell once rode in Norris’s yellow Thing as did Eugene Fodor, who remarked on the postconcert ride back to the hotel, “It’s odd. I guess they don’t give standing ovations in Knoxville,” to which Norris replied, “Oh, they do, when performances deserve them.”

He was tall and slender throughout his life. When I knew him in the 1970s, his bald pate was inadequately covered by a combover, and he wisely began displaying his head’s bare sheen in the 1980s. Like the rest of him, his head was narrow, and looking at him from the side, his forehead and nose were in alignment and descended to an abrupt point at the tip of his nose. His image in profile could have substituted for Eustace Tilley’s on the cover of the New Yorker, with the butterfly replaced by a microphone. A neatly cropped chestnut beard added a bit of strength to his chin.

When I enrolled at the University of Tennessee in fall 1974, I began my formal study of percussion with Michael Combs, the head of the percussion department. During my senior year of high school, I had taken lessons from him on Saturday mornings in his teaching studio on campus. Mr. Combs, as we called him—no student got away with calling him “Mike”—taught high school students like me in order to bring in extra income. During one of my lessons, he asked what I planned to do for college. I had been thinking of attending Walters State Community College, the local two-year college, a five-minute bike ride from my parents home in Morristown. He listened and then calmly explained why that would be a bad decision. He talked about the opportunities I’d have at UT to play in excellent bands and orchestras and how playing alongside musicians who were better than me would push me. After the lesson, he made the same pitch in the lobby of the Music Building to my father, who had driven me the fifty miles from Morristown to Knoxville for the lesson. Mr. Combs explained that many percussionists entering the program were able to cover most of their expenses through a band scholarship, which required service in the marching band in the fall and the concert band throughout the school year.

I auditioned for the band and received a scholarship to fill one of the eight snare drum slots in the Pride of the Southland Band. The cost of attending UT at that time wasn’t high, and the scholarship helped tip the scale toward going to UT. It seemed a small decision at the time, but attending UT instead of WSCC set the stage for everything that followed.

During my first term at UT, I started playing in the percussion ensemble and took weekly private lessons with Mr. Combs. Within a few weeks he had taken my measure as a player and a person and started pulling me in for gigs off campus. When ensembles in town needed a percussionist, they called Mr. Combs, who farmed out reliable students for the jobs. The most desirable gig was playing with the Knoxville Symphony Orchestra, the city’s semiprofessional orchestra. As timpanist for for the KSO, Mr. Combs had an understanding with the orchestra management that he could place three of his students in the contracted percussion positions, without audition. When more than three percussionists were needed, he filled the parts with extras drawn from a pool of over a dozen students.

University of Tennessee percussionists, 1975. Left to right: Faye Harville, Richard Griscom, F. Michael Combs (director), Daniel Sell, Denton Stokes, Bill Woods, Monte Coulter. This small group played concerts at public schools and retirement homes, funded by the American Federation of Musicians’ Music Performance Trust Fund

During this first fall at UT, Mr. Combs pulled me in as as an extra for the opening concert of the orchestra’s 1974–75 season, which featured two difficult works: Richard Strauss’s Ein Heldenleben and Ottorino Respighi’s Feste romane. It was during rehearsals for this concert that I met Norris. Since moving to Knoxville in 1968 to become program director at WUOT-FM, Norris had played violin in the orchestra, and although he rarely practiced, he was better than most of the other violinists and sat in the first violin section at one of the middle stands. By the time I made my first appearance with the orchestra (playing a ratchet, among other things, in Feste Romane), Norris had become the personnel manager for the orchestra, so I had some interaction with him to get paid for the rehearsals and concert. He knew some of the contract percussionists—juniors and seniors in the percussion department—and occasionally talked with them during breaks.

I already knew of Norris because I was an occasional listener to WUOT and had heard him announcing during the afternoons and on Monday nights, when he hosted a show called “Untitled,” a block of three hours when he could program whatever he pleased. For one show, he decided to play the scherzo movements of all nine Bruckner symphonies. He broadcast recordings of recent Knoxville Symphony performances, when they didn’t include major gaffes. He occasionally interviewed people involved in classical music in Knoxville, including not only prominent figures like the conductor of the Knoxville Symphony Orchestra but also a long-time professor of music history at UT, George DeVine, who told stories of his days playing bassoon in the Chicago Civic Orchestra under Frederick Stock.

Interview of George F. DeVine by Norris Dryer on “Untitled,” broadcast on WUOT-FM in either 1977 or 1978. Recorded off the air by Richard Griscom.

A feature of every installment of “Untitled” was a music quiz. Norris played a recording of an obscure piece of music (for example, Franz Liszt’s cantata Christus), and listeners phoned in their guesses. In the 1970s, there was no internet and no Shazam, so listeners were left to rely on their wits and whatever reference books they might have at hand. The only prize for winning was the satisfaction of hearing Norris announce your name on the air. One week, I was the only listener to identify Schumann’s Violin Concerto, and I had arrived at my guess by looking at the article on “concerto” in the Harvard Dictionary of Music (1944) and seeing that the Schumann concerto had been “recently discovered” (in 1937), so I assumed it was still fairly unknown.

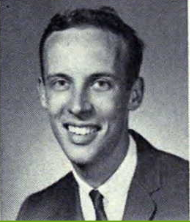

Although it’s natural to assume Norris was a musician who just happened upon a career in broadcasting, he attended Indiana University to major in broadcasting, not music. The entry for Norris in the IU yearbook of 1965—the year he graduated—reads “Dryer, Norris Lee. A.B. Radio and Television; Elkhart; Trees Center, Cult. Ch.; Young Americans for Freedom; IU Orchestra.” Pulling this apart, his bachelor’s degree was in radio and television; his hometown was Elkhart, Indiana; he was in some way affiliated with the Trees Center (a set of military barracks used as student housing after World War II), perhaps as a resident; he was a member of the Young Americans for Freedom (which today is an ideologically conservative group, but for Norris to have been a member it must not have been in the 1960s); and performed in the IU Orchestra.

Norris Dryer in the 1965 Arbutus, the Indiana University yearbook

After graduating, Norris’s first jobs were in Michigan, starting in Big Rapids at WBRN, a commercial station, then moving to WIAA, a public-radio station in Interlochen. Two years later, he moved to WUOT, where he worked for thirty-four years until his retirement in 2003.

Many radio and television announcers use an on-air voice that is distinct from their speaking voice. The enunciation, the rise and fall in pitch, and the cadence are exaggerated and mannered. Norris’s broadcast voice was natural and unaffected—identical to his speaking voice. He sounded the same reading the cast list of an opera recording on “Untitled” as he did telling a story in a bar about the time David Van Vactor showed up drunk at an orchestra afterparty.

On one occasion when the KSO scheduled a work involving a narrator, Norris performed the speaking role. It was Britten’s Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra, a piece that showcases the instruments of the orchestra, first in groups and then individually, bringing them all together for a concluding fugue. During the course of the work, the narrator introduces the groups and individual instruments as they make their appearance. Norris did a straight reading of the text, but he occasionally changed his inflection to put a spin on the sense of a phrase—mischief that was lost on most listeners. The KSO had an excellent principal cellist, Mary Fraley, but the players sitting deep in the cello section were often out of tune and loose in their execution. The narrator’s introduction of the cellos in the Britten score reads, “Cellos sing with splendid richness and warmth. Listen to this fine sound!” When Norris read the second sentence, he emphasized “this” and raised an eyebrow skeptically, suggesting the listener would be hearing anything but a fine sound.

During my last two years at UT, I lived in the Andy Holt Apartments, the largest dormitory on campus, with three other drummers: Monte Coulter, a fellow member of the UT Percussion Ensemble; Mike Berry, a business major who played snare drum in the UT marching band; and Fred Stanin, a geology major who had drummed with Mike in band in high school in Kingsport. The fifteen-story apartment building, built in 1968, was still fairly new, and our apartment was on the thirteenth floor. It was a long elevator ride up and down, and we scoffed at anyone who got on or off at any floor lower than the fourth.

There were two bedrooms. Monte and I shared one, and Mike and Fred had the other. When Mike graduated after my junior year, we didn’t have a fourth person lined up to replace him, so we were assigned a roommate at random. Mark was a shaggy-haired, droopy-eyed sophomore who would have been happier living in fraternity housing than with three upperclassmen. His interest was partying, and although the three of us enjoyed drinking and playing music on weekends, during the week we concentrated on school. Mark went out drinking every night, and he often ended up sleeping on the couch in the living room if he returned after 11:00, when Fred locked the bedroom door.

One Saturday night, as Mark left the apartment to join his friends, Monte asked where he was headed. “We’re going out to egg some queers at the Carousel.” During the 1970s, the gay community in Knoxville had only a few options for socializing, and one was the Carousel, familiar to straights and gays alike as the “gay bar.”

The Carousel came up in a conversation with Norris one day, and he said, “Oh, I’ve been there several times.” I was surprised. “Isn’t that a gay bar?” “Yes, it’s known for that, but there are all types of people there, and not all of them are gay. It’s an interesting place to watch people. You might enjoy going sometime.”

As I think back on that conversation, I wonder whether Norris thought I might be a confused straight—that there was a chance I was gay but conflicted about it. If so, he would have had good reasons for wondering. I had no girlfriend, and I didn’t date. This didn’t seem unusual to me at the time: among the people I spent time with—mostly music majors—I’d met no one I was interested in dating. It was that simple. I felt straight, but hooking up for casual sex didn’t interest me—even if I could have pulled it off, and I’m not sure I could have.

If Norris did have these suspicions and wanted to present an opportunity for me to sort things out, he approached the issue carefully, because I didn’t detect a motive behind his suggestion that I go to the Carousel. We did go one evening, and what he said was true: there was a disco dance floor with all types of people dancing, though there were far more obviously gay men than would have been typical in other bars. I remember four or five people around the table, including one of my roommates, so either a group of us went with Norris or others joined us in the bar.

We sat and watched the dancers on the floor. After half an hour, a young man walked up to our table and greeted Norris, then sat down next to me and put his hand on my leg. I shook my head, and Norris casually intervened and explained. We stayed for another hour, drinking, talking, and watching, before we left. I didn’t return to the Carousel, and I suspect the reason wasn’t that it was a gay club but because I didn’t enjoy dance clubs, straight or gay.

Later that year, Norris was stabbed in the abdomen. I asked him how it happened, and he said it was someone he’d met in a bar (not the Carousel), and his wallet was stolen. (His violin might have been stolen too, because I remember he had to replace his violin at some point after a theft.) I was shocked, but he shrugged it off. “It wasn’t a serious injury and didn’t hurt that much. I’ve felt worse with the flu.”

In high school and college, my awareness of gayness and gay cultural was vague, if it existed at all. I wasn’t equipped to pick up on signs that a person might be gay. This skill developed over time, yet I still miss signals that my wife quickly identifies. When I was in college, despite all the indicators, I didn’t suspect Norris was gay, and I didn’t find out until after I had graduated. I can’t remember when he told me or why he told me, which suggests that it wasn’t presented as a significant revelation. I suspect it came up in a conversation about something else. When I learned, I wasn’t surprised, and it made no difference to me. I don’t think he would have told me if he’d sensed it would have. That’s how he was, and it was all right with me.

I had been a regular listener to WUOT-FM in high school, and ever since I was a kid I’d been fascinated by radio. When I enrolled at the University of Tennessee in 1974, I walked across campus to the Communications & Extension Building, a low-slung semicircle of concrete and glass, just to see the home of the WUOT studios. I didn’t know whether the station employed students, but it was a place I wanted to work. For me, WUOT was the perfect mix of things I loved: classical music, sound recordings, and gadgets with knobs and dials. I can’t remember whether I approached Norris about working at the station or he approached me. What he was able to offer was a few hours a week as a board operator—someone who spins records and plays announcements and promos from prerecorded tapes. The job would involve no announcing, which was fine with me.

The first step to being authorized to operate equipment at any radio station at that time was to secure an FCC radiotelephone third-class permit, and this required a trip to Nashville to take a written exam. I applied for the permit by mail and bought a study guide that covered various rules and practices (the maintenance of logs, requirements for identifying the station) and technical details (the physics of radio waves, the ranges of the radio bands), and some math. I studied the booklet carefully. One Saturday morning, I drove my parents’ car four hours from Morristown to Nashville, took the test in the afternoon, spent the night in the apartment of my high-school girlfriend (then a student at Vanderbilt), and drove back the next day. Within a few weeks, the paper certificate arrived in the mail, and I was authorized to operate radio transmission equipment.

During my four or five years working as a board operator, I used little of what I’d learned from the study guide. What was most important was knowing how to operate the reel-to-reel tape decks, turntables, and 8-track tape deck (used for short promotional announcements) and how to properly connect an input to an output using cables inserted in a patch board in the control room. This knowledge was passed on from the full-time station staff.

The staff of WUOT were an interesting, motley bunch. Because the announcers and board operators worked alone on their shifts, we rarely saw each other, and our interactions were limited to the few minutes it took to exchange information at the end of a shift. “The second turntable is out for repair, so I’ve been working with just the first one. Oh, and there’s a network feed in an hour they want you to record. The blank tape is in the bin.”

The classical-music announcers worked during the day, and the board operators—those of us who did no announcing—worked at night and on weekends. Three people covered the daytime classical announcing: chief announcer Wayne Stagg, music director Glenn Hauser, and occasionally Norris.

Wayne was a charming, reclusive man with straight salt-and-pepper hair and a scraggly beard he would pull at while announcing. As chief announcer, he was responsible for training the board operators, and he showed patience and good humor in his teaching. A few years after I left WUOT, he also left—not only WUOT but radio broadcasting altogether.

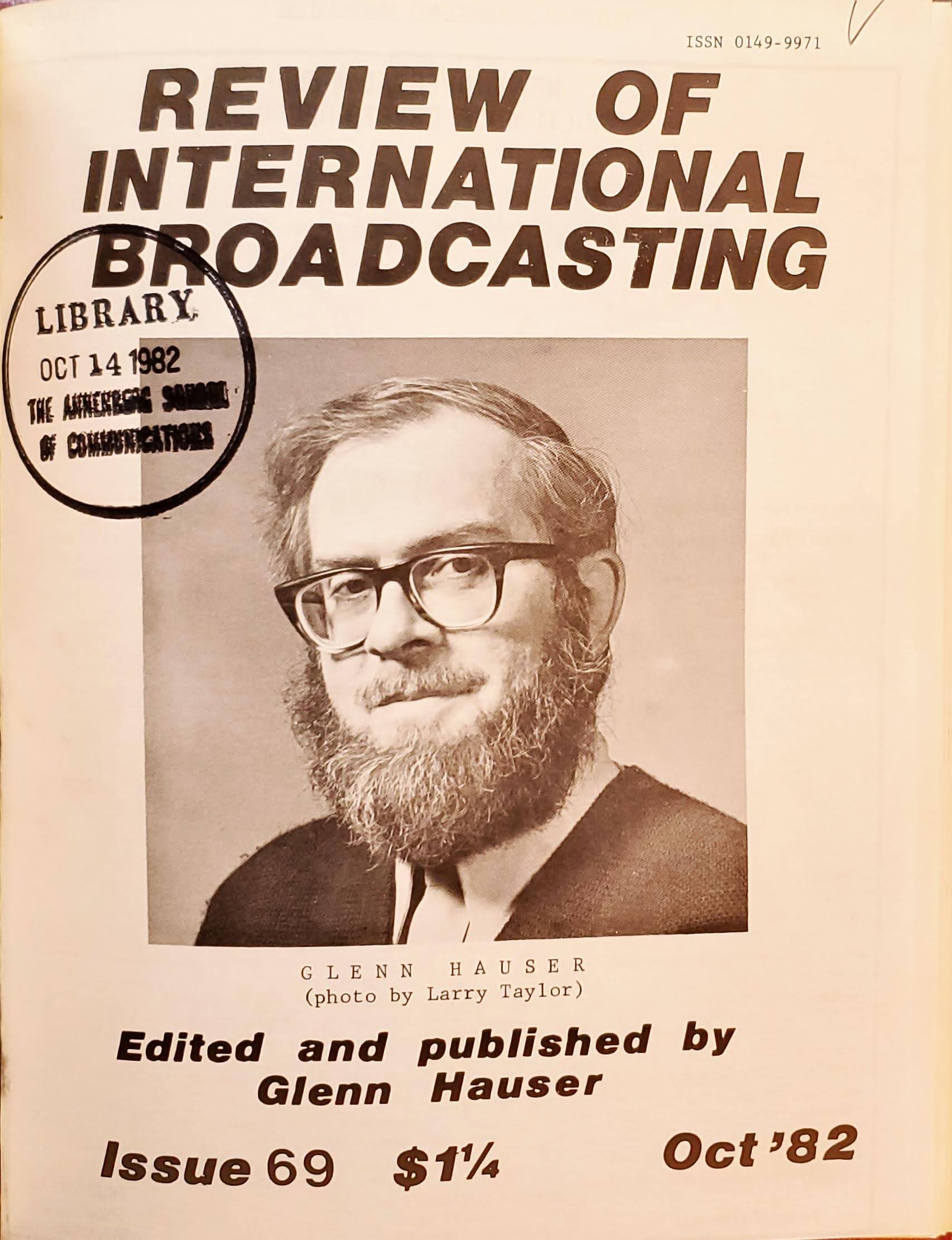

Glenn Hauser, on the cover of the Review of International Broadcasting, no. 69 (October 1982)

Glenn Hauser was best known for the work he did outside WUOT: he was (and continues to be) one of the world’s best-known shortwave radio authorities. In college, I subscribed to his monthly Review of International Broadcasting, a fat pamphlet whose content was typed out by him on 8½” × 11″ sheets, with no blank lines, using an IBM Selectric typewriter and then reduced to fit four pages on the front and back of folded 8½” × 14″ sheets. (Here’s a random page.) A typical issue was forty-eight pages long. His weekly “World of Radio” program, a survey of new programs and transmissions on shortwave, started on WUOT, whose listeners were an unlikely audience. It soon moved off WUOT’s program schedule (I suspect at Norris’s request) and began successful syndication on radio stations around the US and on shortwave stations worldwide.

Subscription information for the Review of International Broadcasting, taken from the cover of issue 44 (October 1980)

Though he wasn’t a musician, he had a good knowledge of classical music and jazz and a strong command of the pronunciation of foreign languages. Despite his expertise and renown, Hauser’s tenure at WUOT was rocky. The challenges came with his interactions with other staff. By the time he left, he and Norris rarely spoke. After working at WUOT for about eight years, he moved in summer 1984 to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, where he continued his shortwave-related work. In the Review he explained his move:

WHY HAS GH MOVED TO FLORIDA?, some of you are wondering. I’ve never lived more than eight years in one place, and was itching for a change of scenery and activities, plus the advantages a larger city has to offer; and cold winters were extremely unpleasant for me. I definitely saw improvements in Knoxville while I was there, but would hardly rate it “the best place to live in America,” as recent publicity had it! I don’t think Fort Lauderdale is the ultimate, either, and foresee another move to the Southwest before another eight years go by—I might have moved there now, but distance-wise, it seemed to make more sense to take the Florida interlude now, while relatively closer. (Review of International Broadcasting, August 1984, p. 2)

As he predicted, he made his next move about three years later, to Enid, Oklahoma, about an hour and a half north of Oklahoma City.

There was some jazz programming on WUOT, ninety minutes at 11:00 pm Sunday through Friday and an hour at 4:00 pm on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. Among the jazz announcers was Ashley Capps, who later made a name for himself as the founder of the Big Ears Festival, for which he won a Tennessee Governor’s Arts Award in 2019. Capps hosted a program of avant-garde jazz one evening a week he called “Unhinged,” a play on Norris’s Monday evening “Untitled” program. (Glenn Hauser came up with his own program, “Unbridled,” broadcast early Saturday evening.)

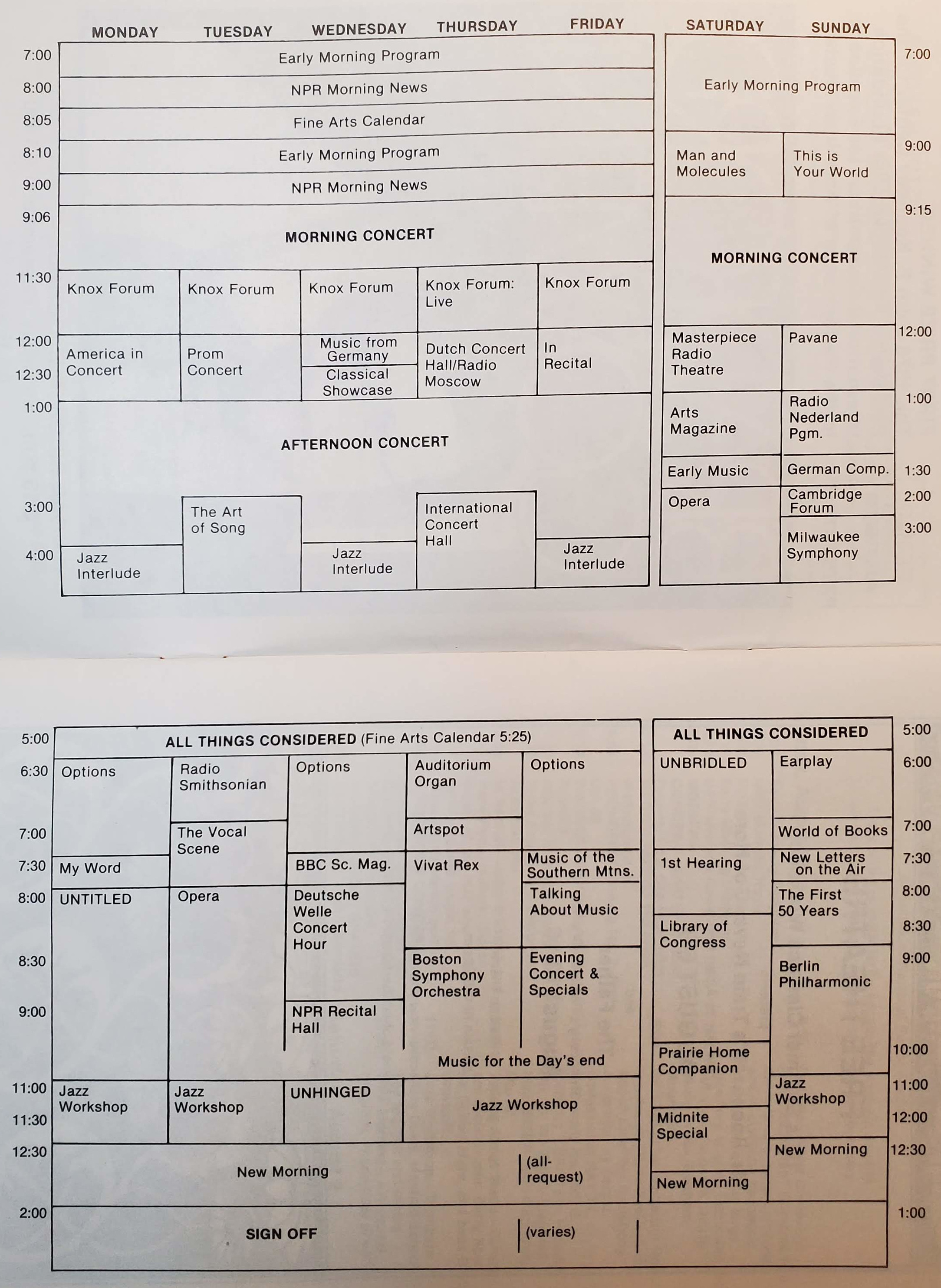

WUOT-FM program schedule for August 1980

We board operators worked in the evening and on weekends, and everything we needed was left for us in the control room in a rolltop bin on wheels: the broadcast log listing the pieces to be broadcast and their duration, the LPs to be broadcast, and a reel-to-reel tape with announcements for the pieces. Norris recorded this tape at the end of his workday. Staff pulled the LPs from the record library and put them in the bin, which he rolled down the hall to a small recording studio to prepare the tape. The first time I used one of his announce tapes, I listened to the first few minutes to get a feel for it, and the sequence was a bit unsettling. “Opening this evening’s concert is George Szell conducting the Cleveland Orchestra in Mozart’s Symphony number forty in G minor. (breath) That was Mozart’s Symphony number forty in G minor with the Cleveland Orchestra under the direction of George Szell.”

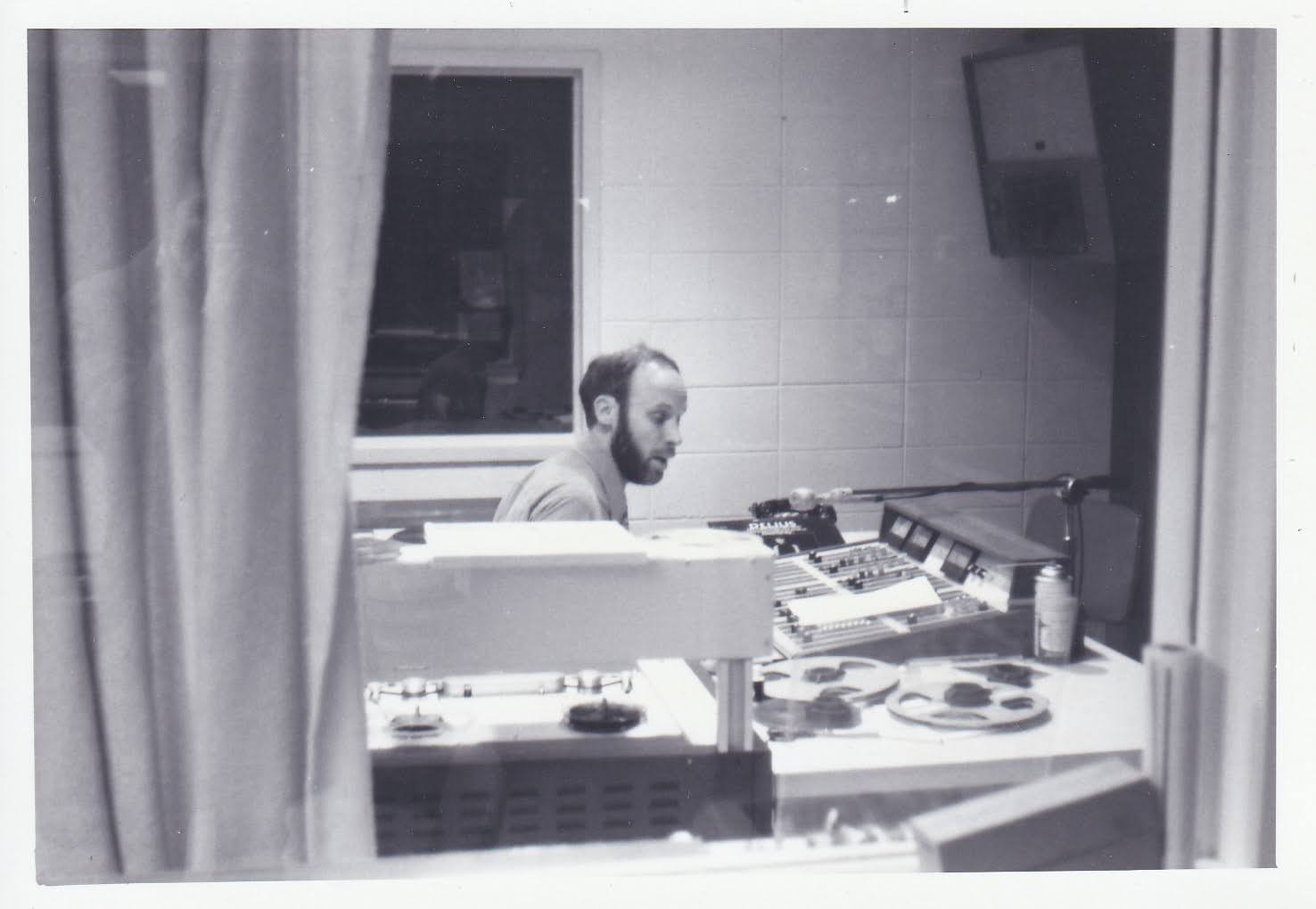

Norris Dryer recording an announce tape in the studios of WUOT-FM (photo by RG, October 1976)

Occasionally the station would go off the air, and we board operators were instructed to go into the transmission room when that happened and press buttons in certain sequence to revive it. Often the button-pushing restored transmission, but sometimes the problem was with the transmitter itself, perched high on top of Sharp’s Ridge, which ran east to west across the northern edge of Knoxville. Most of the city’s major radio and television stations had transmission towers on the ridge—so many that they looked like the needles on a porcupine’s back. WUOT had a transmission engineer on retainer, a hang-dog fellow named Joe Chasteen, who had a drooping moustache and wore his glasses down the bridge of his nose. There was a phone in the control room so we could call him whenever the transmitter couldn’t be revived. Often he could walk the board operator through a successful series of resuscitative steps, but occasionally the problem was the result of something having happened to the transmitter, damage either by the weather or a fallen tree branch.

These transmitter outages could occur at any time of day, and some occurred at night. Joe first stopped by the station to make sure everything was working at the start of the pipeline. Norris said he often could tell from his garbled speech and foul breath that he had been five or six beers into the evening when he got the call. Regardless of his condition, he took his job seriously. He drove up the ridge and even in his drunken state climbed the wire-framed tower to fix whatever might have been wrong. Norris always expected to hear news of his demise after falling off the top of the tower while trying to reconnect a wire.

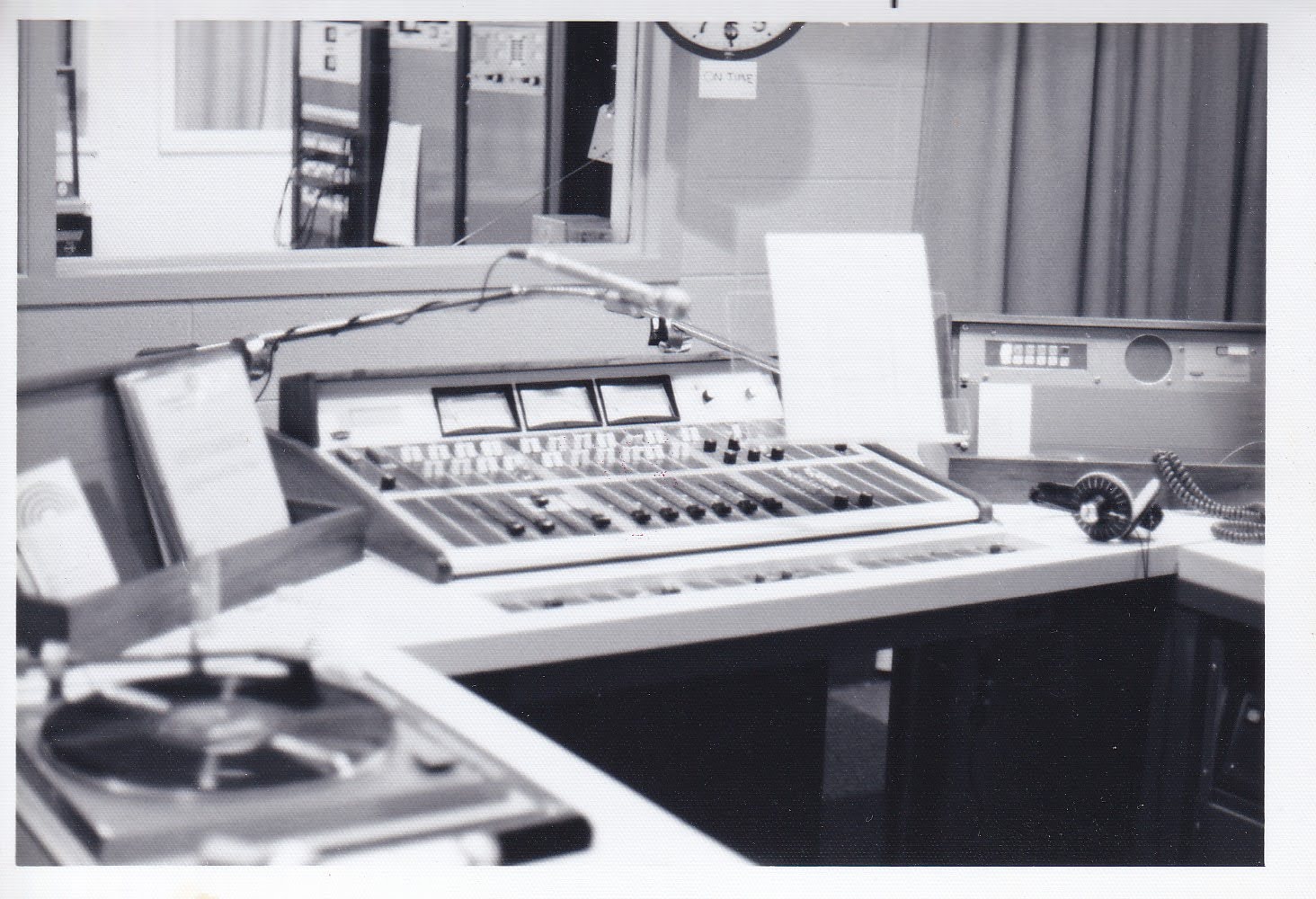

Equipment controlling the transmission to WUOT-FM’s radio tower, with a phone to call the engineer (photo by RG, October 1976)

The control room was also the location of the magical box that brought us the NPR network feed, which was delivered to WUOT from an uplink station receiving transmissions from a Westar 1 satellite. Because the time of the live feed of a program didn’t always align with the WUOT broadcast schedule, we board operators were occasionally asked to patch a reel-to-reel tape deck in the control room into the network feed and record a program off the air for broadcast later. Sometimes I remembered to do this, and other times I didn’t.

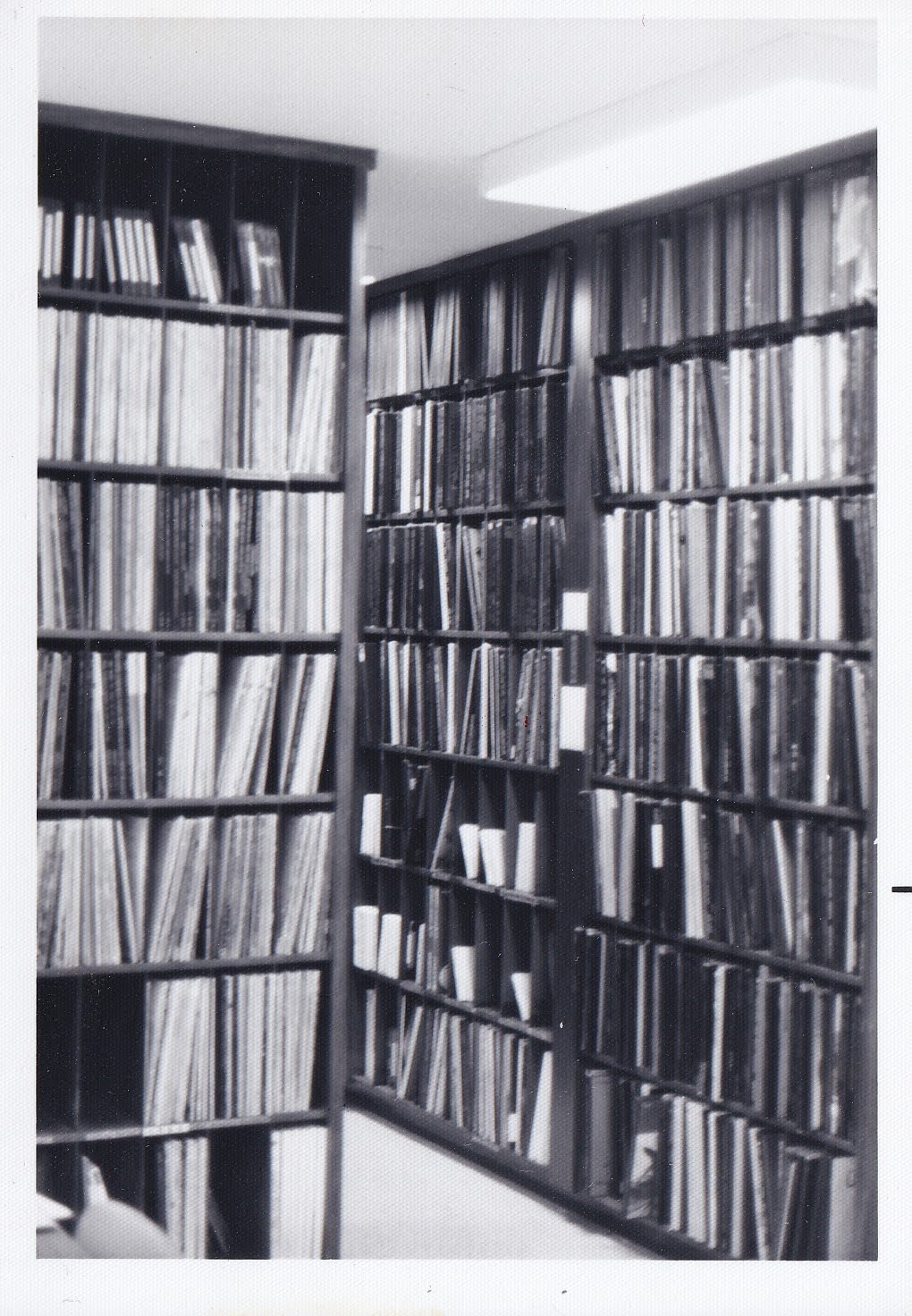

The library of LPs at WUOT (photo by RG, October 1976)

The content broadcast by WUOT came from four sources: microphones in the control room, LPs from the station’s vast collection of thousands, the network feed from NPR (either live or captured on tape), and syndicated programs on tape. These tapes arrived in the mail weekly, shipped in cardboard boxes, and were placed in the bin with the LPs scheduled for that day. Everything in the bin was arranged in the order it would be programmed. The tapes would arrive “tails out,” so the board operator had to place the full reel on the right spindle and then rewind it onto the empty spool on the left before playing it. Occasionally board operators would forget to do this, putting a tails-out reel on the left, and the audio would run backwards—usually for only a few seconds, depending on how alert and sober the board operator was at the time. There would then be a few minutes of dead air while the board operator switched the two reels and rewound the tape.

After one of these gaffes, the rest of the broadcast day would be off by a few minutes, which is probably one reason Norris often built extra time into the LP-and-announce programs. It was helpful to have extra unprogrammed time leading up to programs with a firm start time, like All Things Considered at 5:00 pm on weekdays. Depending on who was behind the board—an announcer or a board operator—this extra time leading up to the hour could be filled by talking (for example, a promotional announcement for an upcoming show) or by “filler music.” The bin always had one or two LPs of guitar or piano music with tracks that lasted one or two minutes for use as filler. As a board operator, I’d draw on these regularly, and to this day, whenever I hear “Leyenda” by Isaac Albéniz played on guitar, I expect it to fade out to the beginning of an NPR program.

The broadcast studio of WUOT-FM. The “On Time” under the clock indicates that it is in sync with NPR’s clock (photo by RG, 1976)

Although WUOT was thought of by most people as a classical-music station, much of its programming was public-radio fare covering a broad range of nonmusical topics: “Man and Molecules,” “This Is Your World,” “Medicine, Mind & Music,” “BBC Science Magazine,” “World of Books,” “Options in Education,” “Masterpiece Radio Theatre.” Still, more than half the special programs were musical or about music. There were weekly concerts by four major orchestras; international concerts from Holland, Germany, Sweden, and the UK; organ music, chamber music, and early music; and blocks of jazz on Sunday and folk music on Fridays.

Over time, I proved myself competent and responsible as a board operator, and because I could rein in—or at least soften—my East Tennessee accent, after a year I was allowed to do some live announcing on the air. When I left UT in 1978 to work on a graduate degree at Indiana University, I came back home to Morristown in the summers and worked twenty-five hours each week at a sales job in the automotive department at the local K-Mart and drove to Knoxville on Friday nights for a regular shift at WUOT. I’d close the K-Mart at 9:30 pm, drive to Knoxville, and sign on at WUOT at 10:30 pm.

On Friday nights, there was an all-request program that ran from 11:30 pm until sign-off at 2:00 am. I’d always wanted to Norris to call this program “You Asked for It,” but he wouldn’t buy it. The requests were made by telephone, and listeners started calling in during the jazz program that preceded the request show. There were faithful listeners to the program, and some of them consistently requested the same piece. After one gentleman asked for Gustav Holst’s tone poem Egdon Heath four weeks in a row, I decided to cut him off.

Because the staff of the radio station were interesting, smart people who had few opportunities to spend time together—and some had never met each other, since the day staff rarely saw the evening staff—Norris decided to host a party for the announcers and board operators at his apartment. It was the last time he would structure a social event around the staff. As I approached his apartment that evening, I suspected I’d find a dozen people busily chattering in groups of two and three, some standing in the corner near the dining room table, others in the kitchen, a few in the living room. When I entered, there was silence, and the eight attendees, all sitting in chairs and couches around a coffee table, looked up to see who had just walked in. I got a beer and sat down at the end of the couch. Discomfort and awkwardness hung heavy in the air. Every few minutes someone spoke up, and someone else replied, but the conversation never took off. As we sat around the coffee table looking down into our beer cans, Norris eventually said, “If this party doesn’t pick up, I’m going to leave and go to a bar.”

“Mozart’s piano concertos are the greatest music ever written,” Norris said one evening at the ball park. “How do you figure that?” I said. “Well, I think most people would agree that Mozart is the best composer who ever lived. And the piano concertos are often said to be his finest compositions. So, that would make them the greatest music ever written.” Many people would quibble with this, but for Norris, Mozart’s music was the pinnacle of musical art, and he often had little appreciation for lesser composers.

In 1975, Mr. Combs organized a trip to the Soviet Union and England for the UT percussion ensemble. The tour was managed by a professional travel company, and in order to make the trip affordable, we had to have a certain minimum number of participants. That number couldn’t be met by the members of the percussion ensemble, so Mr. Combs opened up registration to the general public. Because Norris had never been to the Soviet Union and generally enjoyed the company of the UT percussionists (although he despised Mr. Combs), he joined us on the tour. We performed at conservatories in Moscow and Leningrad, and on the return trip, we performed in London. Little of our time was spent performing, so there were both planned activities (a production of Tchaikovsky’s Iolanthe in the Soviet Union and a concert by the London Symphony in Royal Albert Hall that included Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony) and time on our own.

While in London, I made a trip on my own to the largest music store I could find, and in the dozens of filing cabinets I found scores that weren’t held in the UT music library—works I’d read about but never seen. During high school and my first few years at UT, I was fascinated by the life and music of Igor Stravinsky, and I’d read quite a bit about his last composition, the Requiem Canticles, and listened to a recording of it, but I hadn’t seen a score. This music store had a copy of the work in miniature score, and I happily bought it. That evening, I talked to Norris about my trip to the music shop, and he asked what I had ended up buying. I pulled out the miniature score, and he shook his head. “One of the largest music stores in the world, and you come out with Stravinsky? Do you already own everything by Mozart?”

At the beginning of my senior year, I started thinking about what to do after I graduated. I’d entered UT intending to major in math, but my first quarter of calculus had been so difficult and tedious I quickly moved off that path. Music was what interested me, and it was where I directed my energy. In high school, my only exposure to music professionals had been my teachers—the band director, the choir director. If I wanted to make a living in music, becoming a band director seemed the obvious path, and that’s the one I started down.

The music-education curriculum required music theory and music history courses during the first year, and once I’d been introduced to the academic side of music—to music theory through the colorful Bach-loving-and-Beethoven-hating Walter Hawthorne and to music history through George DeVine—I realized that was where I belonged. I felt I was a different from the typical music student at UT, and my interests didn’t line up well with the music-education curriculum, with its instrumental methods courses (learning how to play the trumpet and clarinet well enough to teach an eight-year-old) and general education courses. I abandoned the music-education program during my sophomore year and joined a small group of music-history majors, whose prospects for employment after college was far slimmer than the music-education majors. To get any kind of job in music history, I would need to pursue an advanced degree.

I talked to Norris about this, and he started lobbying me heavily on behalf of Indiana University, where he had graduated a little over ten years earlier. He told me about the five orchestras and the student and faculty recitals, scheduled for almost every night of the week. He said it would be the perfect place for someone like me who had a strong performance background and wanted to continue playing. He suggested that we make a trip to Bloomington so I could see the campus for myself. We must have made that trip in fall 1977. I don’t remember any of the details of the trip—not even where we stayed, though I suspect Norris reserved rooms in the Indiana Union.

Once Norris had convinced me to pursue an advanced degree at Indiana University, I had to sell the idea to my parents. Although IU offered graduate assistantships, I would need support from them to cover some of the expenses. For many of my friends, this would have been a hard sell, but my parents agreed to it, if not supported it. I applied for a teaching assistantship, and luckily I got one that covered all tuition plus a stipend to help with living expenses. Besides the help my parents provided with my IU expenses, my mother would include a five-dollar bill in most of her weekly letters—four-pages she wrote on Wednesday mornings and I’d receive in Bloomington on Friday or Saturday, just in time to cover the Sunday night dinner not included in the meal plan, if I hadn’t already spent it on a pitcher of beer at Bear’s Place on Saturday night.

During the decades after I left UT—the years at IU, my first job, in the Chicago area, and then subsequent jobs in Louisville and Champaign-Urbana—Norris and I were in touch only occasionally. I often received a ribald card from him near the holidays. Even after the advent of electronic mail, we rarely wrote each other. He was busy living his life, and I was busy with mine. In 2002, I wrote him to let him know about changes taking place in my life, and his reply included some details on changes of his own:

My life is centered around fazing myself out at WUOT, that should be completed by June 30, 2003, being active on the search committee for a new KSO Music Director, (we’ve hired Lucas Richman, Resident Conductor of the Pittsburgh Symphony), starting a campaign for a Knoxville City Council seat with the backing of the Knoxville Green Party, dealing with the responsibilities of an only child regarding my 91 year old parents in Indiana and continuing a nearly 3 year relationship with a 23 year old recovering red neck named Larry, aspects of which could be on a Jerry Springer show.

Either that year or the next, my wife and I had dinner with Norris in Knoxville. As expected, he had aged, but he had not changed in any meaningful way. His stories continued to be entertaining and often outrageous. After that meeting, we fell back out of touch, and it wasn’t until 2020, by casually Googling his name, that I learned of his death in 2014. When I read the online obituary and the tributes, memories surfaced that led me to think back to my days at UT and the influence he had on my career at an important time. I suspect he was puzzled by the direction my career took when I moved into librarianship. When I was finishing graduate school, he sent me job postings for public-radio positions in classical music, and I suspect that’s where he saw my future—following his own career path, which had brought him satisfaction.

I didn’t have the voice for broadcasting though, which became clear when I tried to continue my part-time work at IU’s public radio station, WFIU. I auditioned for the chief announcer, George Walker, who gave me a list of titles in foreign languages (French, German, Italian) to read through. He was gentle in turning me down, but he made it clear I didn’t make the grade for WFIU, whose standards for announcing were higher than WUOT’s. Without a radio-ready voice, my opportunities in broadcasting would have been limited, and I eventually ended up pursuing a degree in library science.

Norris did get me out of Tennessee and into the more challenging environment of Indiana University, where the playing and listening opportunities were everything he had billed them to be. Bloomington was a small town teeming with talented, interesting musicians, and working and living with them put me on the path I ended up taking. Norris’s influence on me was timely, strong, and lasting.