Arpad Joó: A Personal History

Arpad Joo, publicity photo from ca. 1975

One day in 1977, Norris Dryer mentioned he was planning to have lunch with Arpad Joó, the music director of the Knoxville Symphony Orchestra, and asked me if I’d like to join them. He suspected that I’d be interested, and he also knew I’d have the good sense to stay mostly quiet during the lunch. I took him up on the offer, and we set up a time for him to pick me up. Joo was vegetarian and had suggested a Chinese restaurant on the west end of Knoxville where there would good options for him on the menu.

Norris had been key to the orchestra’s hiring of Joo as music director in 1973. During the preceding quarter century, UT music professor and composer David Van Vactor had been conductor of the orchestra, and under his direction, the orchestra had evolved from a loosely organized community orchestra to a semiprofessional ensemble. By 1972, the orchestra was ready for a change, and though I’m sure Norris told me the reasons for Van Vactor’s departure, I can’t remember them or even whether Van Vactor was ready to give it up the post or was pushed out.

In the 1970s, the School of Music at Indiana University was the largest in the country, and its conducting program was strong. When the Knoxville Symphony Orchestra management launched their search for a new conductor, Norris made a convincing pitch: because the orchestra’s financial resources were limited, it was to the orchestra’s advantage to attract a rising star rather than to try to sign an established conductor, and they might be able to discover a promising advanced student in Bloomington. Norris made the trip and talked to several members of the faculty, who helped him identify good prospects. Among them was the twenty-four-year-old Arpad Joó, a Hungarian pianist and conductor. They met, and Norris made his case for the KSO and encouraged him to apply.

During the 1972–73 season, each of the finalists for the position conducted one of the orchestra’s subscription concerts. A curmudgeonly friend of Norris’s was in the audience for each of the concerts, and after Joó’s spring 1973 audition, he told Norris that when Joó walked across the stage, he thought, This one probably has some talent, because his tux isn’t pressed.

His concert was a success, he was hired, and Joó and his wife, singer Nancy Ogel, moved from Bloomington to Knoxville. Much of the early publicity spotlighted his age, and this was lost on me. I could see how it would be unusual for a twenty-five-year-old to be hired as music director of an orchestra, but he was eight years my senior, and that span seemed large—the bridge between adolescence and adulthood. For most members of the orchestra, he was a kid, but for me, his composure and gravitas was unlike anything I saw in myself or those around me. He was a twenty-five-year-old who behaved like someone twice his age, conducting with confidence and authority—mostly from memory—and with ease and grace.

When he made his entrance at concerts, his lanky frame bounded onto the stage, stooped over, like Groucho Marx but with a high-spirited bounce to the step. He was a handsome man, with curly black hair swept back from his forehead and a neatly trimmed, thick beard. His English was good, but he communicated best during rehearsals through facial expressions. He could speak paragraphs through a raised eyebrow.

More important than his skill on the podium was his ability to command control over the orchestra, which comprised a mix of professionals (mostly UT faculty) in the principal chairs and front stands, talented students in the middle, and community musicians filling in the back. Some of the community members had been with the orchestra for decades and hadn’t practiced seriously in decades. Joó, like most conductors of his generation, was positive, encouraging, and generous with praise. He placed demands on the musicians, but unlike the generation of conductors that preceded him, he didn’t become angry and insulting when a musician couldn’t deliver what he expected.

We occasionally had a taste of the old-school approach when we worked with guest conductors. In October 1976, Arthur Fiedler, the renowned conductor of the Boston Pops, was brought in for a concert. His publicity photos always showed him smiling, and he was often engaged in some light-hearted comic business. During our rehearsals we quickly got to know the real Arthur Fiedler. As we rehearsed the overture to Rossini’s overture to Semiramide, Fiedler worked over a passage involving an exposed trumpet part. A note was out of tune, and the principal trumpet couldn’t hear it. Fiedler repeated the phrase. After the third repetition, he barked, “You, sir, shouldn’t be in here! You should be out on the corner selling fish!”

Joó had high expectations, but he accepted the limits of some of the members—including a few of the principal players—and he worked within those constraints when he could and ignored them when he couldn’t. During concerts, clarinets might shriek, horns might crack, a long note in the first violins might sound like a microtonal smear, but Joó kept smiling. At most, he would raise an eyebrow then cock his head to the side with a light shrug.

Still, he pushed the orchestra to improve its musicianship. When he arrived, he required members to reaudition, which weeded out some of the worst legacy players. He programmed music that riskily explored the technical limits of the orchestra—works like Feste Romane and Ein Heldenleben. By programming these challenging pieces, Joó made the orchestra members feel there was an expectation for them to be good enough to play them. The music also challenged listeners used to light overtures and Beethoven symphonies, and I imagine most subscribers were bemused or angered by them, but the experience the orchestra gained by learning these challenging scores carried over to its performance of music the subscribers were used to hearing.

Nancy Ogel, from the 17 October 1974 program of the Knoxville Symphony Orchestra

Joó’s wife, Nancy Ogel, was an accomplished singer who had studied at IU with Martha Lipton, who had made over four hundred appearances with the Metropolitan Opera. Joó occasionally programmed works to feature his wife as a soloist. On the October 1974 concert that included Ein Heldenleben and Feste romane, Ogel was the guest soloist and sang arias and songs by Wagner, Verdi, Puccini, Debussy, and Richard Strauss. A couple of years later, Joó programmed a concert performance of Puccini’s La Boheme, in which Ogel sang Mimi.

Ogel was an excellent singer, but as the years passed, she appeared on the concert schedule less frequently, and other singers were brought in as featured soloists, including a Knoxville-born operatic singer who had sung once at the Metropolitan Opera but was best known for providing the voice of a Disney princess for an animated feature in the 1950s. During my first year at UT, she sang with UT’s marching band during a football half-time show in Neyland Stadium, and that was my first experience hearing her sing. Her voice was large, with the broad vibrato you might expect from an opera singer, but it was also slightly under pitch—just enough to sound sour. When she sang with the band, she was only in her mid-forties, so her voice was still young, and the wide vibrato and the intonation problems couldn’t be attributed to age. It sounded as though she might have broadened the width of her vibrato to mask the pitch issues. If the wobble is wide enough, the correct pitch will be in there somewhere. Afterward, the director of the band, Dr. Jay Julian, a cold-hearted, cruel taskmaster of the old school of conductors, let us know he hadn’t been pleased with her performance, which he felt had tarnished the reputation of his band. At our next rehearsal, he quipped, “She’s a has-been that never was.”

A few years later, this same singer was scheduled as a soloist for a Knoxville Pops concert. This was the period when the Boston Pops, under Arthur Fiedler’s direction, had become popular. The Boston Pops had a regularly scheduled program on public television, and their albums of light classical music were cross-over best sellers. Many orchestras around the country scheduled their own “pops concerts” to capitalize on the Boston Pop’s popularity. Annual “Knoxville Pops” concerts took place in the main arena-sized hall of the Knoxville Civic Coliseum. A four-foot-high platform fringed with black cloth was set up for the orchestra on the buffed concrete floor, and the audience sat on folding chairs arranged around six-foot round-top tables covered with white tablecloths. Waitstaff took orders off a menu that included peanuts, pretzels, hot dogs, a variety of soft drinks, Michelob (75 cents), and set-ups for harder BYOB alcohol. The menu in the program for the 1976 pops concert—the one that Arthur Fiedler (“you should be out on the corner selling fish”) conducted—noted that “there will be no sales during the performance of the Liszt Concerto” so attention would be directed to that evening’s soloist, Arpad Joó, who was often a soloist with the orchestra and always played Liszt.

Two years later, the Knoxville-born celebrity opera singer was scheduled as the featured artist for the May 1978 Knoxville Pops concert. On the program were orchestra highlights from Rocky and Star Wars, Ravel’s “Bolero,” and the overture to Bernstein’s Candide, and the opera singer would be performing selections from operettas and musicals, including Annie, The Sound of Music, and My Fair Lady. This would also be the last concert Joó conducted as music director. The concert program announced that he had taken the position of music director for the Calgary Philharmonic, and Zoltan Rozsnyai would succeed him in the fall.

Several of us in the KSO percussion section had been in the marching band for the opera singer’s performance a few years earlier, so our expectations weren’t high. When she arrived at the rehearsal, she was very much the diva, wearing a long, colorful dress and flashing a lustrous smile. Joó welcomed her with deference and grace. After the orchestra played its introduction, she started singing, and her voice was as it had been with the band—wavering heavily and under pitch. As Joó conducted, he smiled faintly, but his left eyebrow impulsively shot up at particularly offensive notes. We ran through all of her selections, and Joó thanked her. She left, smiling and bowing as we applauded her, and we proceeded to rehearse the rest of the program.

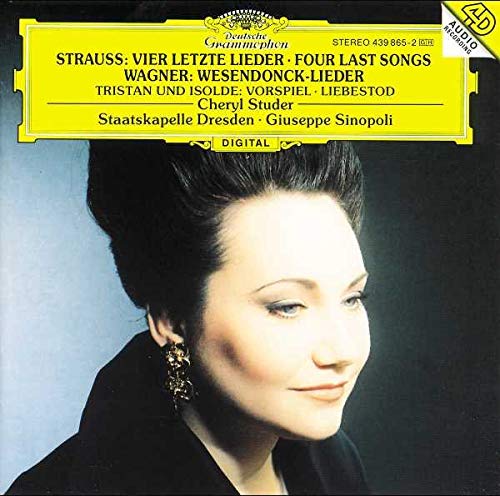

For the dress rehearsal—or perhaps the actual performance, I’m not sure—Costa called in sick, and on short notice UT student Cheryl Studer was asked to perform the pops concert in her place. She sang beautifully, with little rehearsal beyond a coaching session with Joó, who was beaming throughout the performance. The quality of the singing was likely lost on most of the audience members, and I’m sure some were disappointed to be hearing a mere student instead of a celebrity opera star. And I doubt any of them realized they were hearing one of the first public performances by a singer who would attract thousands of listeners to European opera houses during the next decade, leading to performances at the Metropolitan Opera beginning in the late 1980s and continuing to 2000. In the 1990s, she appeared on dozens of opera recordings and made a highly regarded recording of songs and arias by Strauss and Wagner on Deutsche Grammophone with Giuseppe Sinapoli.

I never learned the full story of why Cheryl Studer was brought in for the concert. The celebrity singer could truly have been sick, she could have feigned sickness to avoid embarrassment (I doubt this), or Joó was so frustrated by her performance at the rehearsal that he refused to perform with her. I’m sure I talked to Norris Dryer about the saga, and he either didn’t know what happened or, more likely, chose to be discrete, and it was one of many topics I forgot to bring up with him when we met again in 2003.

Deutsche Grammophon compact disc of Cheryl Studer performing Strauss and Wagner with the Staatskapelle Dresden directed by Giuseppe Sinopoli (1994)

I remember few details of my lunch with Norris and Arpad Joó. I recall Joó ordered a dish with stirfried eggplant, which was not part of the East Tennessee cuisine I had grown up with. Its name and appearance seemed exotic. Everything about the lunch was magical to me; I was seeing this brilliant musician outside the context of the orchestra hall. I don’t remember music coming up in our discussion. Although I remained quiet and listened during most of the meal, I did pose a few questions. When Joó mentioned in passing that he slept only five hours each night, I couldn’t help asking how that was possible. He said his practice of Buddhism included meditation, and the breathing exercises provided rest without sleep.

When Joó left Knoxville in 1978 for Calgary, Linda Case, the coprincipal violinist of the KSO, moved with him and became principal violinist for the Calgary Philharmonic. After three years in Calgary, she moved to Ithaca, New York, where she taught at Ithaca College. Joó’s wife, Nancy Ogle, after leaving Knoxville, eventually joined the faculty of the School of Performing Arts at the University of Maine.

Early in the 1980s, money from a Calgary oilman allowed Joó to make several successful recordings in Hungary, with Hungarian orchestras, of works by Bartók and Kodaly using newly developed digital technology. Accounts in the Calgary press, though, suggest that Joó had a troubled relationship with the orchestra’s management. The board tried to remove him several times, and he ended up leaving Calgary for a position in Madrid in the late 1980s. For the remainder of his life, he conducted mostly in Europe, and his appointments were with minor European orchestras. After a rapid rise in the 1970s and early 1980s, his conducting career ended quietly, and he died from a heart attack in Singapore in 2014. There were no obituaries in major newspapers, and it was several months before a few blogs reported his death.